| |

CARL ANDRE "POEMS"

26 mars - 30 avril 2009

CARL ANDRE

POEMS

26 mars 2009 â 30 avril 2009

Vernissage : jeudi 26 mars 2009 de 18 h Ă 20 h.

Galerie Ivana de Gavardie

10 rue des Beaux-Arts

75006 Paris

Exposition ouverte du mardi au samedi de 14 h 30 Ă 18 h 30.

Exposition organisĂ©e par Arnaud Lefebvre â TĂ©l. : 33 (0)6 81 33 46 94

arnaud@galeriearnaudlefebvre.com â www.galeriearnaudlefebvre.com

(Merci de noter qu'une traduction française du texte d'Alistair Rider se trouve en-dessous du texte anglais)

CARL ANDRE'S POEMS: AN INTRODUCTION

ALISTAIR RIDER

Although Carl Andreâs Minimalist sculptures have been exhibited internationally for well over forty years, his poetry remains less well-known. In fact, it has often been regarded by commentators as merely one of the artistâs subsidiary interests, and thus of only marginal relevance to his sculpture. Yet there is a strong case to be made that his beginnings as a creative artist were just as much based in literature and poetry as they were in the visual and plastic arts. More importantly, we might also suggest that for Andre the intense interrogation of text and words, which is so characteristic of the poetry, is an activity which runs parallel to his work as a sculptor. The two endeavours feed and support one another in important ways.

Beginnings

Andre was born in 1935 in Massachusetts, and when he was sixteen he was awarded a scholarship to attend the prestigious bording school at Andover â Phillips Academy. Like many of his generation with an inclination for culture and the arts, Andre developed there an appreciation for poetry, and it was thus as a teenager that he started to compose verse seriously. For the 1950s, the curriculum in English literature at the school was highly progressive, and by the time he left in 1953 Andre would have been on conversant terms with the major canonical poetic works of European and North American modernism. In fact, when he arrived in New York in 1957 following his military service, he had already been writing in a decidedly modernist fashion for several years. Of these early lyrical efforts, few have survived. The odd ones that drifted into print sport titles such as "Shboom," or "Susannah in Italy" â they are impressionistic and fragmentary, and in spite of their literary stylishness, they do not appear to have satisfied him that much.

During this period in the late 1950s, Andre was living a hand-to-mouth existence. His first job in New York was as an assistant editor for a publishing firm that specialised in text books, and thus words and script were a constant aspect of his daily life. He stayed in the post for only for a year, and then after that conducted editing work on a purely free-lance basis, when and if he needed the money. His companions were largely old school friends from Phillips Academy, and closest to him were Hollis Frampton, Michael Chapman, Frank Stella and Barbara Rose. All would go on to enjoy extraordinary careers â Frampton as an experimental film-maker, Chapman as a cameraman in Hollywood, Stella as a painter, and Rose as an art critic. But it was largely Frampton and Chapman who shared and supported Andreâs literary interests. Frampton was an enthusiastic advocate of the modernist poet Ezra Pound, and it was through Framptonâs library of books that Andre encountered Poundâs writings on sculpture. He read the poetâs memoir of Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and also his famous essay on Constantin Brancusi. It goes without saying that thanks to his friendship with Frampton, Andre would also become well versed in Poundâs poetry â in "The Cantos" in particular.

Over the course of these years Andreâs writing would become increasingly experimental. During the winter of 1958-1959, he set to work on a comic novel about a boy called Billy Builder who enjoys a fascination with science and an affinity for young women. It runs to around fifty pages. One of his friends sent it to a serious and well-established publishing house, Grove Press, who sat on it for several months before turning it down. Yet in the mean time, Andre was already writing more comic novels. But now they were so brief that the longest runs to merely a few dozen words. In total he produced twenty-two of them. Number 12 reads: âI work very hard. My employer is pleased with my regularity. Underneath I have a devil-may care attitude. How else could I live in hell so long?â In fact, exploiting the conventions of a particular literary or artistic form would develop into a major preoccupation for Andre, and it is a theme he pursues in much of his poetry.

Yet we might go even further than this, and suggest that the kind of verse which Andre came to produce by around 1960 is so un-lyrical and works so effectively against the standards of sense-making that it undoes most of the conventional assumptions about the very form of poetry itself. Certainly, Hollis Frampton was utterly fascinated by his experimentations with written language, and suggested in a letter to a friend that Andreâs poems would âstrike harder at the supposed norm of English verse than anything else has in 40 years.â(1) Indeed, in certain respects many of Andreâs works do resemble little laboratory experiments designed to test how much pressure poetry might withstand without dissipating, or becoming a substrate of something else altogether.

Typewriting

One of the reasons why Andreâs poems are so unusual is that they veer towards the visual to an uncommon degree. In an interview in 1975, he suggested that if initially poetry had begun as an oral art closely associated with music and song, then his work was quite distanced from this tradition. In contrast, his poetry had its roots merely in writing, reading and printing. This was not about mapping language onto music, but âlanguage mapped onto some aspect of the visual arts.â(2)

The distinctive visual quality of this work derives mainly from the fact that almost all of Andreâs poems are produced using a manual typewriter, and much of his early poetry amounts to an exploration of the possibilities afforded by a mechanized writing machine. One of the salient characteristics of the typewriter is that it automatically sets down text in grid-like rows and columns. Because it dedicates an equal space on the page for each letter, Andre could arrange words according to his own organising system, and the outcome invariably would attain an enticingly tidy, visual format. For instance, in a poem called âblue...stepâ which dates from October 1964, the stanzas are each six lines long. One new word is inserted at the start of every line, shunting the others along to form a distinctively serrated right-hand margin:

blue

wash blue

cut wash blue

sing cut wash blue

word sing cut wash blue

cry word sing cut wash blue

This preoccupation with presentational effects might be thought to imply a disinterest in the sounds that words make. But Andre never disregarded the rhythms of spoken language: he merely aimed to cancel out the effects of poetic metre in favour of a monotonous drone. In one group of poems, for instance, Andre would repeat the same letter of a word literally dozens of times, thus allowing him to generate a field of print from merely half a sentence, or a handful of nouns. The outcome is not entirely illegible, but the effort demanded to read even a line is abysmal. âThe word ânoâ voiced for 15 seconds has a dramatic effect different from the word ânoâ voiced at its normal durationâ, Andre pointed out in a letter to his friend Reno Odlin.

âTry reading aloud aaaaannnnnyyyyypppppaaaaasssssaaaaagggggeeeee aaaaattttt aaaaannnnn aaaaabbbbbnnnnnooooorrrrrmmmmmaaaaalllllyyyyy slow rate and note how duration effects pitch and stress.â

Not without reason did the artist Robert Smithson later call his poems ârigorous incantatory arrangementsâ.(3) It should be apparent, though, that Andreâs search for a series of notational effects for altering the rhythms of reading could never have been written without the typewriter to provide the annotation. Andre has never learnt to type properly, and later confessed that all his typewritten poems had been produced by hitting the keys with the finger of one hand. But for him this was important in that it made the act of setting them down all the more machine-like. âIt was like actually embossing or applying physical impressions on to a pageâ, he later explained, âalmost as if I had a chisel and was making a cut or a dye and making a mark on metal.â(4)

Historical subjects

Until 1964 Andre had never exhibited a single sculpture in public. His opportunity finally came in October of that year when he was invited by the curator E.C. Goossen to participate in a group show at the Hudson River Museum at Yonkers, New York. By then Andre was twenty-nine, and up to that point his sculptures were known only to his close circle of friends. Some of his poems had been published in "All Points Bulletin", a slim newsletter which his friend Reno Odlin produced on a mimeograph machine and mailed out to interested parties. But this was a tiny affair. In fact to those who knew him in 1964, it would have been far from obvious that Andre would go on to enjoy a prestigious career as a sculptor. In fact, during the years 1962 and 1963 he barely appeared to have made much three-dimensional work at all. The initial flurry of production which occurred in 1959, when, inspired by Constantin Brancusi, he had started to cut and carve works in wood on the floor of Frank Stellaâs studio had all but been forgotten by the early 1960s. During these years, Andre was working as a freight brakeman on the Pennsylvania Railroad in New Jersey, and his circumstances prevented him from producing anything of a sculptural nature. He lacked both the resources and the studio space. Instead, his creative activity was oriented almost exclusively towards his very particular and unusual form of poetry.

For much of the first half of 1963, Andre busied himself with a long and elaborate epic poem called "America Drill." Reno Odlin typeset a segment of it, and produced a handful of copies to distribute to friends, yet Andre seems to have had little sense as to how it might be published and disseminated more widely. The entire typed poem runs to forty-three pages â not lengthy in the big scheme of things, but in terms of the levels of energy he expended on it, it is undoubtedly a substantial work. It was the culmination of dozens of shorter trials and dry runs, and the subject had been preoccupying him for several years. The poem is composed exclusively of quotations gathered from an eclectic range of sources, and which are arranged according to an intricate yet meticulously pre-ordained system based on prime numbers.

In ambition, the work is comparable in certain respects to Michel Butorâs book-length poem "Mobile: Study for a representation of the United States", in that this too is an attempt to define the essence of the American nation in its historical entirety.(5) Butor embellishes his poem with citations from travel guides, historical sources, manuals, street signs â the book is eminently readable. Andreâs use of citation is, however, rather less approachable, and there is something deeply bewildering and almost horrifying about the way he splices together his words and phrases. It is a poem which almost places the nature of âreadingâ itself in question.

The texts from which the quotations comprising "America Drill" are derived include publications on the aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, a history textbook on the anti-slavery insurrectionist, John Brown, a nineteenth-century account of the indigenous Wampanoags from Massachusetts, and a couple of volumes of Ralph Waldo Emersonâs diaries. The sources might seem eclectic, and they are very reflective of Andreâs personal interests. Yet their selection is also revealing, in that he chose them because in his mind these various historical episodes were paradigmatic of the political and cultural fate of the United States. In fact, Andre would turn to these subjects again and again in his poetry.

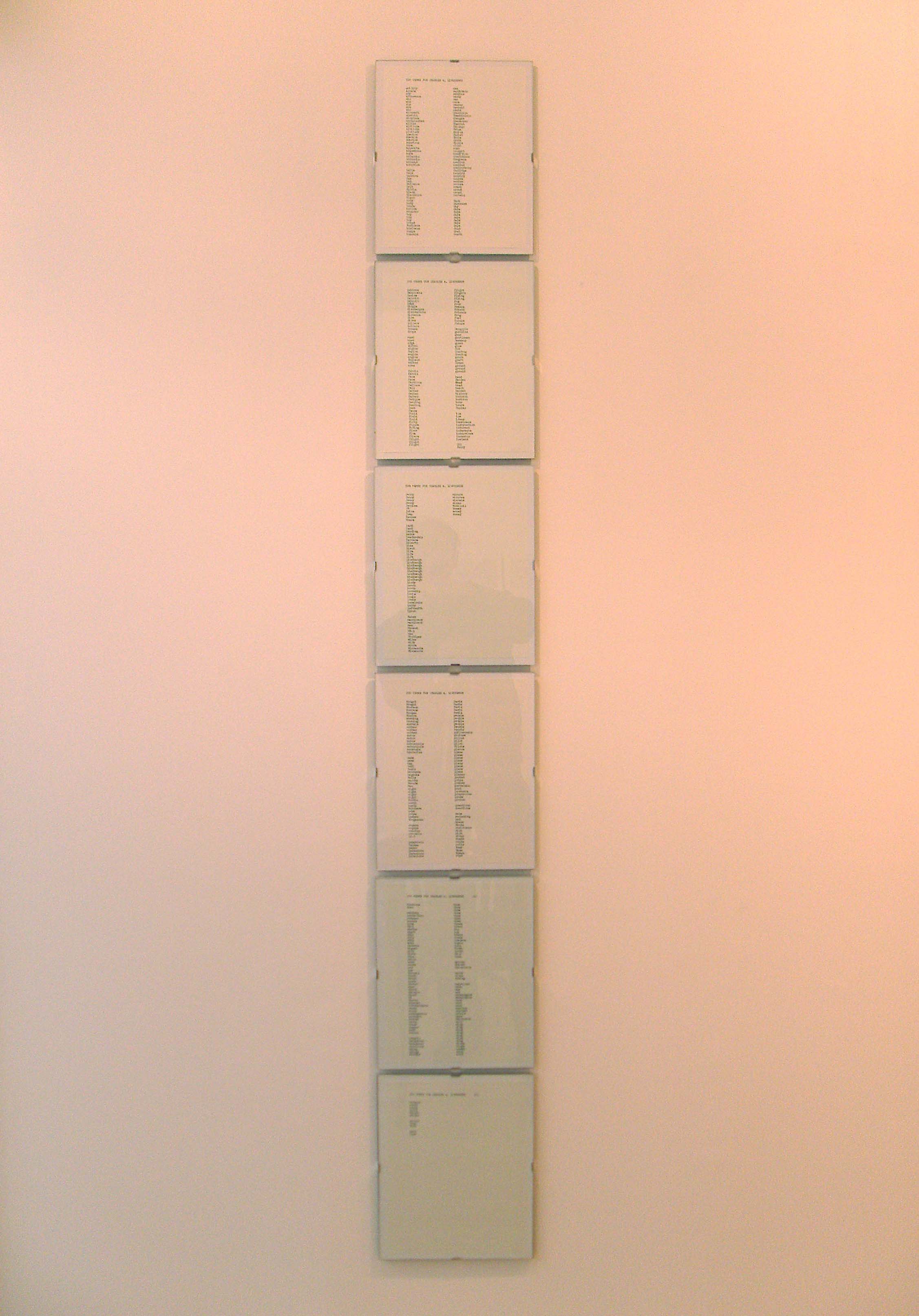

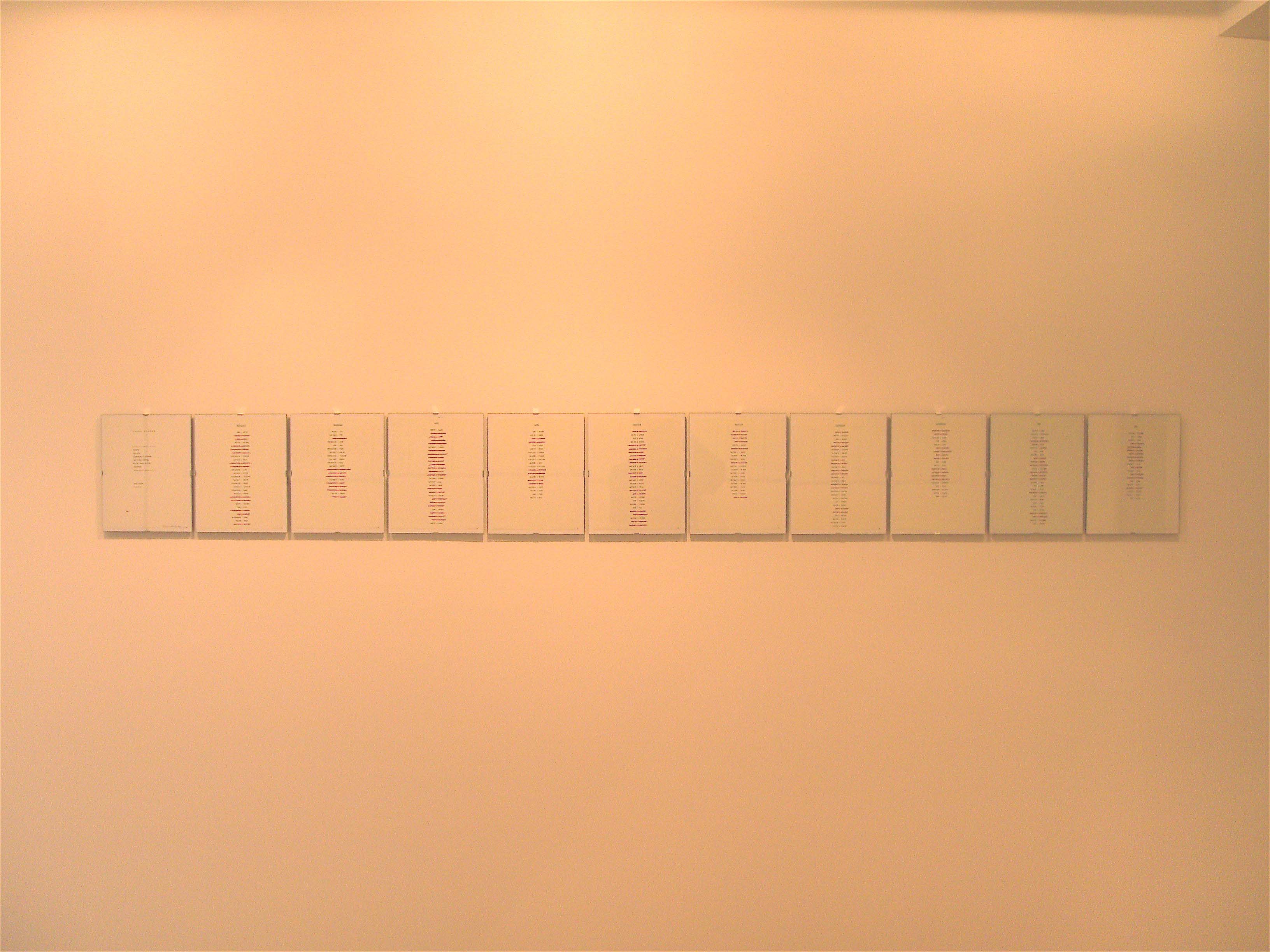

For instance, the work "500 Terms for Charles A. Lindbergh" (which is on display in this exhibition) reflects just one of these privileged episodes. Andre was fascinated by the famous aviator who completed the first solo flight across the Atlantic in May 1927; he had read the biography of Lindbergh by Kenneth S. Davis, and seems to have concurred with Davis that Lindbergh was a singularly unusual man â a person who prized reason far higher than feeling, and who was considerably more at home with complicated machines than with individuals. Andre seems to have understood Lindberg as a type of allegorical figure, representative of a certain trend within the national psyche itself.

Likewise, Andreâs interest in the Wampanoags in Massachusetts stemmed from a similar concern with the cultural and political demise of the indigenous peoples who lived along the northern Atlantic seaboard prior to the arrival of European settlers in the seventeenth century. For Andre, their fate raised intractable questions about the legitimacy of the United States itself. The poem "Three Sachem" (which is also included in this exhibition) is again representative of this particular interest.

Citation

As will be apparent from even a cursory glance at these two particular works â "500 Terms for Charles A. Lindbergh" and "Three Sachem" â Andre may well be alluding to distinct historical subjects, yet the poems themselves consist merely of strings of words selected from source texts. As a means of constructing poetry, this comes across as highly unusual, and deserves considerable attention.

The very notion that poetry might be composed exclusively from citations, or even lists of individual words, was being explored relatively widely in the 1950s and 1960s, and the trend is certainly not unique to Andre alone. In the United States, we might think for instance of the experimentations of the so-called language poets such as Jackson Mac Low, or the works which John Ashbery included in his collection "The Tennis Court Oath". Similarly, William Carlos Williams incorporates dozens of citations from âfound textsâ into his book-length poem, "Paterson". Collectively, these explorations of poetic form might be said to undermine the very conventions of âlyricâ, inasmuch as lyric presupposes a purified, unified voice belonging a distinct authorial subject. Instead, a collage aesthetic starts to predominate, in which broken syntax, isolated words and unconventional techniques in type-setting help to dismantle the basic premises of the western poetic tradition.

If we wanted to establish a proper literary context for Andreâs type-written poems, then these poets would certainly warrant a mention, and, more to the point, we might suggest that Andreâs work amounts to an important contribution to this larger trend. Yet it is important to recognise that Andreâs inspiration does not seem to have stemmed from these poets. Nor was he especially influenced by the chance poetics of John Cage, who was so influential for many of Andreâs contemporaries. Certainly, his work bears little association with the group of artists now affiliated with the Fluxus group. Instead, Andreâs thinking seems to have been oriented largely by his close study of an earlier generation of American modernists, most notably the poetics of Ezra Pound, and, to a lesser degree the innovative and highly distinctive prose style of Gertrude Stein.

In 1963 Andre described Poundâs use of words in "The Cantos" as possessing a very particular âplastic and Constructivist qualityâ â a statement which is especially revealing, since it exposes a distinctive aesthetic value which we can now also recognise in his mature sculptures.(6) Andreâs understanding of Poundâs poetry seems to have been informed by two sources â Ernest Fenollosaâs small pamphlet "The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry", and the writings of the Poundian scholar Hugh Kenner. Fenollosa was a sinologist whose work Pound had always championed; after Fenollosaâs death and at the request of Fenollosaâs widow, Pound had been invited to edit his papers, and the poet espoused his ideas throughout his life. Fenollosaâs key hypothesis was that Chinese script was profoundly different from other languages, in that he believed that this was a kind of writing which simply knows no grammar. Unlike German or Latin or Japanese, Chinese words are not constrained by tags and inflections to ordain their rightful sentence position. Nor is there any distinction between nouns and verbs, so that a single term might act at the same time as either a noun, or a verb, or an adjective. This led Fenollosa to propose that there was an extreme concrete vividness to Chinese writing, and it was this quality which Pound attempted to emulate in his poetry.

It was Hugh Kenner who explicitly draws the connection between Fenollosaâs understanding of Chinese script and Poundâs texts in his 1951 publication, "The Poetry of Ezra Pound" â a work which certainly would have been familiar to Andre. Through references to Poundâs essays, Kenner makes the case that in the poetâs symbolist work Pound generated descriptive impressions by merely setting down on the page lists of concrete particulars. In fact, Kenner suggests that just as we might gain a feeling for a personâs tastes by perusing their collection of books, so too do we gain an intelligible sense from poem that consists simply of a list of disconnected phrases, which at first sight appear to have no clear connection.(7) Kenner lays great emphasis on the fact that Pound understood the central task of the poet to be one of naming things accurately and precisely. It was a principle which Andre too would adopt, and he too came to believe that âcalling things by their right namesâ was an act of fundamental significance.(8)

Andre once told Hollis Frampton that his decision to reduce his poetry merely to isolated words had come to him at 3am one night during the winter of 1959, whilst he was working a shift as a brakeman on the Westbound Hump of the Greenville Railroad Yards in New Jersey.(9) But again it should be stressed that Andre was not the first to have wanted to break down poetry to this primary level. We might think, for instance, of William Carlos Williams, for whom the notion of constructing a poem from isolated words was one he too took very seriously. Yet poets such a Williams had always struggled with the question of how they might do this without resorting merely to the non-poetic, or prosaic.(10) Andreâs outlook, on the other hand, is entirely different. He chose very deliberately to confine himself exclusively to the prosaic.

Andreâs poem "500 Terms for Charles A Lindbergh" is typical of his works which are composed by selecting individual words from source texts, and then ordering them on the page according to simple and self-evident criteria, which, in this case, is by alphabetical listing. Whatever we might make of this gesture, poetry conceived in this way is clearly not understood to be an act of âthe imaginationâ, or even âcreativityâ. Instead, it seems rather more comparable to the cool, dispassionate rigours of data processing. More profoundly, it is a kind of poetry which accepts clearly and plainly that a poem is composed of nothing more and nothing less than words, and that it is not the responsibility of the poet to invent words, but merely to select them, and that, ultimately, all the potential and available words are listed in dictionaries.

We might also suggest that Andreâs understanding of poetic writing as a set of interchangeable and permutable parts, selected largely from pre-existing sources, provides a very clear analogy with Andreâs sculptures. After all, the sculptures are also composed of arrangements of separate and separable particles, and Andre never begins work as an artist until he has at his disposal a limited series of units which he can then aggregate.

Dissemination

By 1965 Andreâs career as a sculptor was slowly taking off: in that year the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York agreed to represent his work, and he had two solo exhibitions with them, before transferring to the Dwan Gallery in 1967. As his focus was shifting to sculpture, it is perhaps not surprising that his relationship to his poetry also changed. In fact, Andre began to use the stylistic techniques which he had developed in his poetry in order to produce written statements about his sculptures. These expository poems Andre now categorises as âplanesâ, and a number were published in exhibition catalogues in lieu of prose statements.(11) For instance, in the catalogue for the famous group exhibition, âPrimary Structuresâ at the Jewish Museum in 1966, Andre provided a four stanza plane as a means of introducing viewers to his sculptural art.(12) It comprises exclusively of four-letter nouns. Andreâs contribution the exhibition was the sculpture "Lever", a work which consists of a single row of 137 firebricks that run along the floor. Visitors to the exhibition might have expected to find in the catalogue some kind of textual explanation or rationale from Andre. Instead they encountered a strange word-list. Yet it is clear that both the words in the plane and the firebricks comprising the sculpture are set down, unit by unit, like masonry. And just as there is no use of bonding material to hold these firebricks in place, so the words are free from grammatical fixatives. Clearly, Andreâs text is not exegesis. These nouns are not merely reporters on an action happening elsewhere, but are, in themselves, "effecting" action.

Certainly, from a very early stage critics were aware that for Andre the textual and sculptural were activities which were strikingly interrelated, and that he was just as equally preoccupied with the properties of words as he was with the qualities of materials. In fact, in interviews in the latter years of the 1960s Andre himself often facilitated the comparison by pointing very explicitly to the connections between his poems and the sculptures. It was, in other words, the artistâs reputation as a sculptor which provoked public interest in his poetry, and to this day his poems have received little or no consideration from parties who are not already familiar with Andreâs status as an artist.

The question, however, was how might Andreâs poems be best presented within an art context? It seems fair to suggest that even from an early stage Andre was not happy to see his text-based works reproduced in books in merely a generic typeface selected by the publisher. To have them presented in this way would undermine the key visual qualities of his works, principally because it would overlook the significant role the typewriter performs in their production. In essence, it was the imprint of the inked letter on the page which always has been so important for Andre, and since paper embossed with text is his preoccupation, reproducibility and dissemination simply was never a concern for him. Thus, in around 1967, Andre started to exhibit and sell individual manuscripts of his poems as works in their own right. Later, sheets of typewriting paper and carbon copies were framed on the walls in the same way as might be prints and drawings.

Photocopying

In 1968, Andre collaborated, along with ten other artists in the production of a catalogue which is often referred to nowadays as "The Xerox Book". The artists, who included Robert Barry, Daniel Buren, Jan Dibbets, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, N E Thing Co., Robert Smithson and Lawrence Weiner, were each allocated by their editor, Seth Siegelaub, twenty-five pages with which to explore the qualities of Xerox reproduction.(13) For the time, the book was mass produced â in total one thousand copies were published. But that was not the principle purpose; the goal was to invite the artists to explore the qualities of this relatively new technology. Andreâ contribution was to drop twenty-five small square pieces of cardboard onto the screen of the copier, one at a time. Each time he dropped one of the squares, he made a photocopy of where it lay. The result is a set of pages which record the process of its own making â a theme Andre was also exploring in his sculptures at that time.(14)

The following year, Siegelaub approached Andre and proposed that he might act as an editor of an anthology of his poems, which would be produced in conjunction with the Dwan Gallery. Again the technology of the Xerox machine would be used. The advantage of using the photocopier seems to have been that it would preserve the visual characteristics of the poems, at least to a certain degree. Andre divided his poetry into seven sections, each of which would comprise a volume in its own right. These were: "Passport," (1960), "Shape and Structure," (1960-65), "A Theory of Poetry," (1960-65), "One Hundred Sonnets," (1963), "America Drill," (1963), "Three Operas," (1964) and "Lyrics and Odes" (1969). The resulting seven volumes were bound in black plastic ring-binders, and in total only thirty-six editions were produced. It seems fair to suggest that Andre was not especially happy with the outcome. Some pages of the poems are cropped badly, and the quality of the reproduction is, in some instances, relatively low.

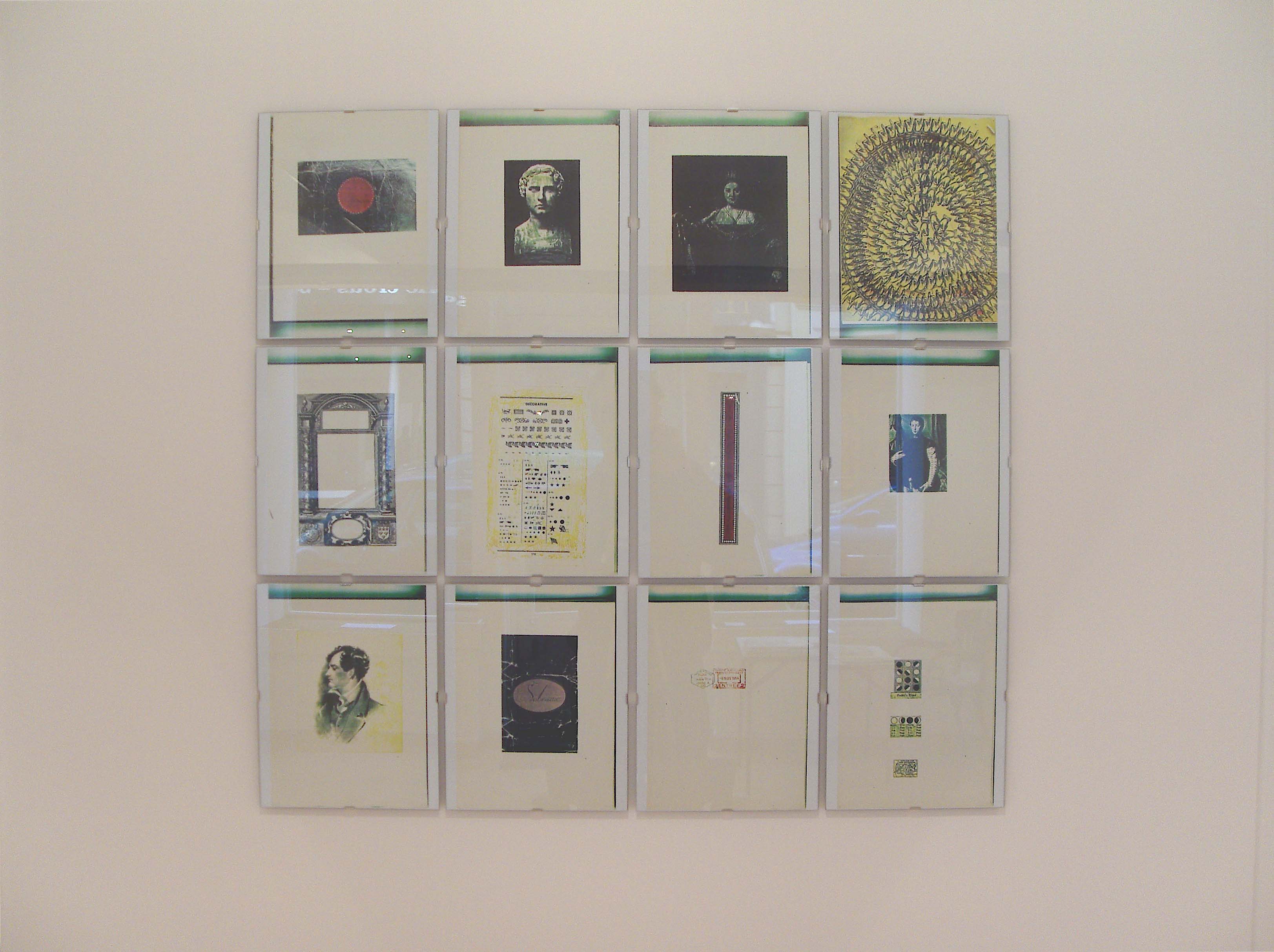

However, these experiments with photocopying seemed to have been of interest to Andre, and over the next two decades he started to experiment with photocopies as a means of disseminating his poetry. What interested him was not the possibility of potential limitless reproduction, it should be emphasized, but the distinctive characteristics of photocopied text â the way that blocks of darker shading can emerge, or the degree to which text fades, and so on. Back in the mid 1950s, Andre had worked for a spell in his home city of Quincy as an office boy at the Boston Gear Works, and one of his duties had been to operate a primitive copying machine that duplicated engineering blueprints. In fact it might be suggested that Andreâs interest in strange distortions and effects of this form of printing technology might be said to have been provoked in part by those early experiences. In the early 1970s, Andre was granted access to a colour photocopying machine, which, at the time, was a brand new and unexplored technology. He was particularly fascinated by the strange acidic colours it generated, and he made a limited number of copies from "Passport." Although "Passport" is often associated with the poems, is in fact a scrap-book of various drawings, pictures, stamps, documents and news clippings that were of interest to him as a young artist in New York. In these colour photocopies, however, the pages look entirely different, and the outcome is an extraordinary set of prints, full of uncomfortable, clashing colours and peculiar visual effects.

Over the years, Andre has produced very limited sets of photocopies of some of his poems, and to this day this remains the principle means by which the poems are disseminated. Although Andreâs copies are not exactly limited editions, each reproduction does bear an index number on the back. Moreover, since the vast majority of the original manuscripts are now housed in public museum collections, or are in private collections, it is unlikely that any further copies will be generated from the originals.

Andre has always considered each copy as unique. As a notion, this might strike us as potentially contradictory, since we might well believe that the very idea of photocoping implies the possibility of making paper prints cheaply and (potentially at least) without limit. Yet in a way, Andre is an artist who very often uses materials and resources which "look" as though they might be replicated ad infinitum, but in fact are not. Think, for instance, of his works from the 1960s made from industrially produced bricks â such as "Lever", from 1966. A row of bricks running along the ground seems to suggest so clearly that the line could be extended indefinitely. Yet Andre used a very particular and limited number of them â 137 â and if any of these bricks were to be removed, or if further ones were to be added, then in Andreâs eyes the work would be destroyed. In other words, whilst Andreâs art very often embraces the idea of the possibility of endless, serial repetition, it also contains a very powerful injunction against that logic. Indeed, the same might be said of Carl Andreâs photocopied poems.

Notes:

(1) Hollis Frampton, Letter to Reno Odlin, 11 March 1964, in "Hollis Frampton Letters," Second Edition, Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre, 2002, p. 119.

(2) Carl Andre in an interview with Lynda Morris, p. 14; reprinted in "Cuts: Texts, 1959-2004," ed. by James Meyer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), p. 212.

(3) Robert Smithson, âA Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Artâ [1968], in "Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings," ed. by Jack Flam (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1996), pp. 79-80.

(4) Paul Cummings, âTaped Interview with Carl Andreâ, 1973; reprinted in "Cuts: Texts, 1959-2004," p. 212.

(5) Michel Butor, "Mobile: Study for a representation of the United States," trans. Richard Howard (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963)

(6) Carl Andre, in Carl Andre et Hollis Frampton,

"Twelve Dialogues: 1962-63", The Press of the Nova Scotia School of Art

and Design and New York University Press, Halifax, 1980, p. 37.

(7) Hugh Kenner, "The Poetry of Ezra Pound," p. 84.

(8) See Phyllis Tuchman, âAn Interview with Carl Andreâ, "Artforum," vol. 8, no. 10 (June 1970), pp. 55-61, p. 60.

(9) Carl Andre, in Carl Andre and Hollis Frampton, "Twelve Dialogues: 1962-63," p. 77.

(10) William Carlos Williams perhaps articulates this admiration for single words in his essays on Marianne Moore and Gertrude Stein in "Imaginations" (London: McGibbon & Kee, 1970).

(11) See James Meyer, âCarl Andre: Writerâ, in "Cuts: Texts, 1959-2004," p. 3.

(12) See Carl Andreâs entry in Kynaston McShine, "Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors," exhibition catalogue, New York, Jewish Museum, 1966.

(13) "Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Daniel Buren, Jan Dibbets, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, N E Thing Co. Ltd , Robert Smithson, Lawrence Weiner," Exhibition Catalogue, ed. by Seth Siegelaub, 1969.

(14) For a discussion of Andreâs contribution to "The Xerox Book," see Alexander Alberro, "Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity" (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), pp. 136-140.

Biography:

ALISTAIR RIDER teaches at the School of Art History at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, and lectures on post-war American art. He is writing a book on the poems and sculptures of Carl Andre which will be published next year by Phaidon. Currently he is researching the impact of ecological consciousness on artists and critics in the late 1960s, and is planning a wide-ranging exploration of artistsâ use of materials during the 1960s and 70s.

This text ©Alistair Rider, March 2009

LES POĂMES DE CARL ANDRE : UNE INTRODUCTION

ALISTAIR RIDER

Bien que les sculptures minimalistes de Carl Andre aient Ă©tĂ© exposĂ©es internationalement depuis bien au-delĂ de quarante ans, sa poĂ©sie reste moins connue. En fait, elle a Ă©tĂ© considĂ©rĂ©e par les commentateurs simplement comme un des intĂ©rĂȘts subsidiaires de lâartiste, et ainsi dâune pertinence seulement marginale par rapport Ă sa sculpture. Pourtant il y a un trĂšs fort argument Ă dĂ©fendre que ses dĂ©buts dâartiste crĂ©atif prennent tout autant leur origine dans la littĂ©rature et la poĂ©sie que dans les arts visuels et plastiques. De façon plus importante, nous pourrions aussi suggĂ©rer que pour Andre lâintense interrogation du texte et des mots, qui est si caractĂ©ristique de la poĂ©sie en gĂ©nĂ©ral, est une activitĂ© qui marche de pair avec son travail de sculpteur. Les deux tentatives se nourrissent et se soutiennent lâune lâautre trĂšs significativement.

Les débuts

Andre est nĂ© en 1935 dans le Massachussetts, et quand il a eu seize ans il a remportĂ© une bourse pour Ă©tudier au prestigieux internat dâAndover â La Phillips Academy. Comme beaucoup dâautres de sa gĂ©nĂ©ration avec un penchant pour la cuture et les arts, Andre y a dĂ©veloppĂ© un sens critique de la poĂ©sie, et ainsi dĂšs son adolescence il a commencĂ© Ă composer sĂ©rieusement des vers. Pour les annĂ©es 50, le programme dâĂ©tudes en littĂ©rature anglaise Ă lâĂ©cole Ă©tait largement avancĂ©, et au moment oĂč il a quittĂ© lâĂ©cole en 1953 Andre a dĂ» sâĂȘtre familiarisĂ© avec les travaux poĂ©tiques canoniques majeurs du modernismme europĂ©en et nord-amĂ©ricain. En rĂ©alitĂ©, quand il est arrivĂ© Ă New York en 1957 Ă la suite de son service militaire, il Ă©crivait dĂ©jĂ depuis plusieurs annĂ©es dâune maniĂšre rĂ©solument moderniste. De ces efforts lyriques du dĂ©but, peu dâentre eux ont survĂ©cu. Ceux qui se sont vus imprimĂ©s sont singuliers, et jouent de titres comme "Shboom", ou "Susannah in Italy" â ils sont impressionistes et fragmentaires, et malgrĂ© leur Ă©lĂ©gance littĂ©raire, ils nâont pas paru lui plaire tant que ça.

Durant cette pĂ©riode Ă la fin des annĂ©es 50, Andre vivait au jour le jour. Son premier travail Ă New York a consistĂ© Ă ĂȘtre assistant Ă©ditorial pour une maison dâĂ©dition qui Ă©tait spĂ©cialisĂ©e dans les manuels, et donc les mots et ce qui touche Ă lâĂ©criture imprimĂ©e Ă©taient un aspect constant de sa vie quotidienne. Il a gardĂ© cet emploi pendant seulement un an, et ensuite a travaillĂ© comme Ă©diteur de textes pour son propre compte, en fonction de ses besoins dâargent. Ses compagnons Ă©taient en majoritĂ© des anciens amis dâĂ©cole de la Phillips Academy, et les plus proches de lui Ă©taient Hollis Frampton, Michael Chapman, Frank Stella et Barbara Rose. Tous ont par la suite joui de carriĂšres extraordinaires â Frampton comme cinĂ©aste expĂ©rimental, Chapman comme camĂ©raman Ă Hollywood, Stella comme peintre, et Rose comme critique dâart. Mais câĂ©tait surtout Frampton et Chapman qui partageaient et soutenaient les intĂ©rĂȘts littĂ©raires dâAndre. Frampton Ă©tait un dĂ©fenseur enthousiaste du poĂšte moderniste Ezra Pound, et câest par la bibliothĂšque de livres de Frampton quâAndre a rencontrĂ© les Ă©crits de Pound sur la sculpture. Il a lu le livre de mĂ©moires du poĂšte sur Henri Gaudier-Brzeska et aussi son fameux essai sur Constantin Brancusi. Il va sans dire que grĂące Ă son amitiĂ© avec Frampton, Andre a aussi acquis une bonne connaissance de la poĂ©sie de Pound â des Cantos en particulier.

Au cours de ces annĂ©es, lâĂ©criture dâAndre deviendra de plus en plus expĂ©rimentale. Pendant lâhiver de 1958-1959, il se mit Ă travailler sur un roman comique au sujet dâun garçon appelĂ© Billy Builder qui avait une grande attirance pour la science et une affinitĂ© pour les jeunes femmes. Il se dĂ©roule sur environ cinquante pages. Un de ses amis lâa envoyĂ© chez un Ă©diteur sĂ©rieux et bien Ă©tabli, Grove Press, qui lâa laissĂ© dormir pendant plusieurs mois avant de le refuser. Toutefois dans lâintervalle, Andre avait Ă©crit dĂ©jĂ davantage de romans comiques. Mais ils Ă©taient dĂ©sormais si brefs que le plus long ne dĂ©passe pas quelques douzaines de mots ; au total il en a produit vingt-deux. Le numĂ©ro 12 se lit : « I work very hard. My employer is pleased with my regularity. Underneath I have a devil-may care attitude. How else could I live in hell so long? » En fait, exploiter les conventions dâune forme littĂ©raire ou artistique particuliĂšre prendra une place de plus en plus prĂ©pondĂ©rante chez Andre, et câest un thĂšme quâil poursuit dans la majoritĂ© de sa poĂ©sie.

Cependant nous pourrions mĂȘme pousser plus loin, et suggĂ©rer que le type de vers quâAndre sâest mis Ă produire aux alentours des annĂ©es 60 tourne tellement le dos Ă la poĂ©sie lyrique et sâoppose si efficacement aux standards de lâapport de sens quâil dĂ©truit la plupart des hypothĂšses conventionnelles sur la forme prĂ©cise de la poĂ©sie elle-mĂȘme. Certainement, Hollis Frampton Ă©tait sous lâemprise de ses expĂ©rimentations sur le langage Ă©crit, et suggĂ©ra dans une lettre Ă un ami que les poĂšmes dâAndre « frapperaient plus fort la norme supposĂ©e du vers anglais que quoi que ce soit dâautre ne lâa fait en 40 ans. »(1) Ă vrai dire, par certains cĂŽtĂ©s, on voit bien que de nombreux travaux dâAndre ressemblent Ă des petites expĂ©riences de laboratoire destinĂ©es Ă tester combien de pression la poĂ©sie peut supporter sans se dissiper, ou devenir entiĂšrement un substrat dâautre chose.

LâĂ©crit Ă la machine

Une des raisons pour lesquelles les poĂšmes dâAndre sont si inhabituels est quâils tournent au visuel Ă un degrĂ© peu commun. Dans une interview en 1975, il suggĂ©ra que si la poĂ©sie avait initialement commencĂ© par ĂȘtre un art oral Ă©troitement associĂ© Ă la musique et au chant, alors son travail Ă lui Ă©tait complĂštement Ă©loignĂ© de cette tradition. Par contraste, sa poĂ©sie avait ses racines uniquement dans lâĂ©crit, la lecture et lâimprimĂ©. Il ne sâagissait pas de faire que le langage sâapplique sur la musique, mais que « le langage soit appliquĂ© sur un aspect quelconque des arts visuels. »(2)

La qualitĂ© visuelle distinctive de ce travail dĂ©rive principalement du fait que presque tous les poĂšmes dâAndre sont produits Ă lâaide dâune machine Ă Ă©crire, et une bonne part de sa poĂ©sie du dĂ©but revient Ă une exploration des possibilitĂ©s offertes par une machine Ă Ă©crire mĂ©canique. Une des caractĂ©ristiques saillantes de la machine Ă Ă©crire est quâelle met automatiquement le texte en rangĂ©es et colonnes disposĂ©es en grilles. Parce quâelle attribue un espace Ă©gal sur la page pour chaque lettre, Andre pouvait arranger les mots selon son propre systĂšme dâorganisation, et le rĂ©sultat atteignait invariablement un format visuel plaisant et bien ordonnĂ©. Par exemple, dans un poĂšme intitulĂ© « blueâŠstep » qui date dâoctobre 1964, les strophes ont chacune six lignes de long. Un nouveau mot est insĂ©rĂ© au dĂ©but de chaque ligne, qui fait avancer les autres pour former une marge droite distinctivement dentelĂ©e :

blue

wash blue

cut wash blue

sing cut wash blue

word sing cut wash blue

cry word sing cut wash blue

Cette prĂ©occupation pour les effets de prĂ©sentation paraĂźtrait impliquer un dĂ©sintĂ©rĂȘt pour les sons que les mots produisent. Mais Andre nâa jamais nĂ©gligĂ© les rythmes du langage parlĂ© : il visait simplement Ă annuler les effets du mĂštre poĂ©tique en faveur dâun bourdon monotone. Dans un groupe de poĂšmes, par exemple, Andre rĂ©pĂ©tera la mĂȘme lettre dâun mot littĂ©ralement des douzaines de fois, lui permettant ainsi de gĂ©nĂ©rer un champ imprimĂ© de seulement la moitiĂ© dâune phrase, ou dâune poignĂ©e de noms. Le rĂ©sultat nâest pas entiĂšrement illisible, mais lâeffort exigĂ© pour lire mĂȘme une ligne est abyssal. « Le mot « non » prononcĂ© pendant 15 secondes a un effet dramatique diffĂ©rent du mot « non » prononcĂ© Ă sa durĂ©e normale », Andre a indiquĂ© dans une lettre Ă son ami Reno Odlin. « Try reading aloud aaaaannnnnyyyyypppppaaaaasssssaaaaagggggeeeee aaaaattttt aaaaannnnn aaaaabbbbbnnnnnooooorrrrrmmmmmaaaaalllllyyyyy slow rate and note how duration effects pitch and stress. » [« Essaye de lire Ă voix haute un passage quelconque Ă une vitesse anormalement lente et note la maniĂšre dont la durĂ©e agit sur la hauteur et lâaccent. »]

Ce nâest pas sans raison que lâartiste Robert Smithson a effectivement appelĂ© plus tard ses poĂšmes « des arrangements incantatoires rigoureux ».(3) Il devrait ĂȘtre apparent, toutefois, que la recherche par AndrĂ© dâune sĂ©rie dâeffets de notations pour altĂ©rer les rythmes de lectures nâaurait jamais pu ĂȘtre rĂ©alisĂ©e sans la machine Ă Ă©crire pour procurer lâannotation. Andre nâa jamais appris Ă taper correctement, et il a admis plus tard que tous ses poĂšmes Ă©crits Ă la machine avaient Ă©tĂ© produits en frappant les touches avec le doigt dâune seule main. Mais pour lui câĂ©tait important car cela rendait lâacte de les mettre par Ă©crit dâautant plus semblable Ă une machine. « CâĂ©tait en rĂ©alitĂ© comme graver en relief ou appliquer des impressions physiques sur une page », a-t-il expliquĂ© plus tard, « presque comme si jâavais un ciseau et faisais une coupe ou un colorant et faisais une marque sur le mĂ©tal. »(4)

Les sujets historiques

Jusquâen 1964 Andre nâa jamais exposĂ© une seule sculpture en public. LâopportunitĂ© lui est finalement venue en octobre de cette annĂ©e-lĂ quand il a Ă©tĂ© invitĂ© par le commissaire E.C. Goosen Ă participer Ă une exposition collective au Hudson River Museum Ă Yonkers, New York. Ă ce moment-lĂ Andre avait vingt-neuf ans, et jusquâalors ses sculptures nâĂ©taient connues que de son cercle dâamis proches. Quelques-uns de ses poĂšmes avaient Ă©tĂ© publiĂ©s dans "All Point Bulletin", une mince circulaire que son ami Reno Odlin produisait sur une machine Ă polycopier et expĂ©diait aux parties intĂ©ressĂ©es. Mais câĂ©tait une toute petite affaire. En fait pour ceux qui le connaissaient en 1964 il aurait Ă©tĂ© trĂšs peu Ă©vident quâAndre continuerait Ă jouir dâune prestigieuse carriĂšre en tant que sculpteur. En fait, durant les annĂ©es 1962 et 1963 câest Ă peine sâil semble avoir fait des travaux en trois dimensions tout court. Lâagitation de production initiale qui advint en 1959, lorsque, inspirĂ© par Constantin Brancusi, il sâĂ©tait mis Ă couper et Ă sculpter des travaux en bois sur le sol de lâatelier de Frank Stella, avait Ă©tĂ© pour ainsi dire oubliĂ©e au dĂ©but des annĂ©es 60. Pendant ces annĂ©es, Andre travaillait comme serre-freins dans la compagnie de chemin de fer Pennsylvania Railroad dans le New-Jersey, et ses moyens ne lui permettaient pas de produire quoi que ce soit de nature sculpturale. Il lui manquait Ă la fois les ressources et lâespace dâatelier. Au lieu de cela, son activitĂ© crĂ©ative Ă©tait orientĂ©e presque exclusivement vers sa forme trĂšs particuliĂšre et trĂšs inhabituelle de poĂ©sie.

Pour une grande partie des six premiers mois de 1963, Andre a Ă©tĂ© occupĂ© Ă un long poĂšme Ă©pique Ă©laborĂ© appelĂ© "America Drill". Reno Odlin en a fait la composition dâun segment Ă la machine, et a produit une poignĂ©e de copies pour distribuer Ă des amis ; toutefois Andre ne semble pas avoir eu beaucoup dâidĂ©e sur la façon dont il pourrait ĂȘtre publiĂ© et dissĂ©minĂ© plus largement. Le poĂšme entiĂšrement tapĂ© fait quarante-trois pages â pas trĂšs long dans lâabsolu, mais en termes de niveaux dâĂ©nergie qui a Ă©tĂ© dĂ©pensĂ© dessus par lui, câest sans aucun doute un travail considĂ©rable. CâĂ©tait le point culminant de douzaines dâessais plus courts et dâincursions infructueuses, et le sujet le prĂ©occupait depuis plusieurs annĂ©es. Le poĂšme est composĂ© exclusivement de citations regroupĂ©es dâune variĂ©tĂ© Ă©clectique de sources, qui sont disposĂ©es selon un systĂšme enchevĂȘtrĂ©, et pourtant mĂ©ticuleusement prĂ©ordonnĂ©, basĂ© sur les nombres premiers.

En ambition, le travail est comparable Ă certains Ă©gards au poĂšme dâune longueur livresque de Michel Butor "Mobile : Ătude pour une reprĂ©sentation des Etats-Unis", dans la mesure oĂč câest Ă©galement une tentative de dĂ©finir lâessence de la nation amĂ©ricaine dans son entiĂšretĂ© historique.(5) Butor embellit son poĂšme avec des citations de guides de voyage, de sources historiques, de manuels, de panneaux de signalisation â le livre se laisse Ă©minemment lire. Lâutilisation par Andre de citations est, cependant, plutĂŽt moins accessible, et il y a quelque chose de profondĂ©ment dĂ©routant et de presque horrifiant dans la façon dont il raccorde ensemble ses mots et ses phrases. Câest un poĂšme qui met presque la nature mĂȘme de la « lecture » en question.

Les textes dâoĂč les citations composant "America Drill" sont tirĂ©es incluent des publications sur lâaviateur Charles A. Lindbergh, un recueil de textes historiques sur lâinsurgĂ© anti-esclavagiste John Brown, un rĂ©cit du dix-neuviĂšme siĂšcle sur les Wampanoags indigĂšnes du Massachusetts, et un couple de volumes du journal de Ralph Waldo Emerson. Les sources peuvent sembler Ă©clectiques, et elles reflĂštent bien les intĂ©rĂȘts personnels dâAndre. Cependant leur sĂ©lection est aussi rĂ©vĂ©latrice de ce quâil les a choisis parce que dans son esprit ces divers Ă©pisodes historiques furent paradigmatiques du destin politique et culturel des Etats-Unis. En fait, Andre retournera encore et encore Ă ces sujets dans sa poĂ©sie.

Par exemple, le travail "500 Terms for Charles A. Lindbergh" (qui est prĂ©sentĂ© Ă cette exposition) ne reflĂšte que lâun de ces Ă©pisodes privilĂ©giĂ©s. Andre Ă©tait marquĂ© par le cĂ©lĂšbre aviateur qui acheva le premier vol solitaire au-dessus de lâAtlantique en mai 1927 ; il avait lu la biographie de Lindbergh de Kenneth S. Davis, et semble sâĂȘtre accordĂ© avec Davis sur le point que Lindbergh Ă©tait un homme singuliĂšrement inhabituel â une personne qui prisait la raison bien au-delĂ du sentiment, et qui Ă©tait considĂ©rablement plus Ă son aise avec des machines compliquĂ©es quâavec des individus. Andre semble avoir compris Lindbergh comme un type de personnage allĂ©gorique, reprĂ©sentatif dâune certaine tendance au sein de la psychĂ© nationale elle-mĂȘme.

De mĂȘme, lâintĂ©rĂȘt dâAndre pour les Indiens Wampanoags du Massachussets provenait dâune prĂ©occupation similaire pour lâextinction culturelle et politique des peuples indigĂšnes qui vivaient le long de la cĂŽte atlantique nord avant lâarrivĂ©e des colons europĂ©ens au dix-septiĂšme siĂšcle. Pour Andre, leur destinĂ©e posait des questions trĂšs difficiles sur la lĂ©gitimitĂ© des Etats-Unis telle quelle. Le poĂšme "Three Sachem" (qui est aussi inclus dans cette exposition) est Ă nouveau reprĂ©sentatif de cet intĂ©rĂȘt particulier.

La citation

Comme il sera apparent mĂȘme dâun regard furtif sur ces deux travaux particuliers â "500 Terms for Charles A. Lindbergh et Three Sachem" â Andre peut bien faire allusion Ă des sujets historiques distincts, nĂ©anmoins les poĂšmes tels quâils sont consistent simplement en successions de mots sĂ©lectionnĂ©s de textes sources. Comme moyen de construire de la poĂ©sie, ceci paraĂźt fortement inhabituel, et mĂ©rite qu'on s'y arrĂȘte sĂ©rieusement.

La notion prĂ©cise que la poĂ©sie puisse ĂȘtre composĂ©e exclusivement de citations, ou mĂȘme de listes de mots individuels, a Ă©tĂ© explorĂ©e relativement largement dans les annĂ©es 50 et 60, et la tendance nâest certainement pas propre Ă Andre seul. Aux Etats-Unis, nous pourrions penser par exemple aux expĂ©rimentations de ceux que lâon appelle les language poets tels que Jackson Mac Low ou les travaux que John Ashbery a inclus dans sa collection "The Tennis Court Oath". Pareillement, William Carlos William incorporera des douzaines de citations de « textes trouvĂ©s » dans son long poĂšme de la taille dâun livre, "Paterson". Collectivement, on aurait la possibilitĂ© de dire que ces explorations de la forme poĂ©tique attaquent les conventions mĂȘmes de la poĂ©sie « lyrique », considĂ©rant que la poĂ©sie lyrique prĂ©suppose une voix purifiĂ©e, unifiĂ©e, appartenant Ă un sujet-auteur distinct. Au lieu de cela, une esthĂ©tique du collage commence Ă prĂ©dominer, dans laquelle la syntaxe brisĂ©e, les mots isolĂ©s et des techniques non conventionnelles en composition typographique aident Ă dĂ©manteler les prĂ©misses de base de la tradition poĂ©tique occidentale.

Si nous voulons Ă©tablir un contexte littĂ©raire propre aux poĂšmes tapĂ©s Ă la machine dâAndre, alors ces poĂštes justifieraient certainement une mention, et, en serrant plus notre propos, nous pourrions suggĂ©rer que le travail dâAndre se rĂ©sume Ă une contribution importante Ă cette tendance plus large. Pourtant il est important de reconnaĂźtre que lâinspiration dâAndre ne semble pas ĂȘtre issue de ces poĂštes. Ni quâil a Ă©tĂ© spĂ©cialement influencĂ© par la poĂ©sie de hasard de John Cage, qui fut si influente pour beaucoup de contemporains dâAndre. Certainement, son travail comporte-t-il peu dâassociations avec le groupe des artistes maintenant affiliĂ©s avec le groupe Fluxus. Au lieu de cela, la pensĂ©e dâAndre semble avoir Ă©tĂ© largement orientĂ©e par son Ă©tude approfondie dâune gĂ©nĂ©ration antĂ©rieure de modernistes amĂ©ricains, tout spĂ©cialement lâart poĂ©tique dâEzra Pound, et, Ă un moindre degrĂ© le style de prose innovateur et hautement distinctif de Gertrude Stein.

En 1963 Andre a dĂ©crit lâutilisation des mots par Pound dans les Cantos comme possĂ©dant une « qualitĂ© plastique et constructiviste » trĂšs particuliĂšre â une dĂ©claration qui est spĂ©cialement rĂ©vĂ©latrice, puisquâelle expose une valeur esthĂ©tique distinctive que nous pouvons maintenant reconnaĂźtre aussi dans ses sculptures Ă maturitĂ©.(6) La comprĂ©hension par Andre de la poĂ©sie de Pound semble avoir Ă©tĂ© informĂ©e par deux sources â le petit pamphlet dâErnest Fenollosa "The Chinese Written Character as a Medium for Poetry", et les Ă©crits du savant poundien Hugh Kenner. Fenollosa Ă©tait un sinologue dont le travail a toujours Ă©tĂ© dĂ©fendu par Pound ; aprĂšs la mort de Fenollosa et Ă la requĂȘte de la veuve de Fenollosa, Pound fut invitĂ© Ă Ă©diter ses papiers, et le poĂšte Ă©pousa ses idĂ©es tout au long de sa vie. LâhypothĂšse clĂ© de Fenollosa Ă©tait que lâĂ©criture chinoise Ă©tait profondĂ©ment diffĂ©rente de celle des autres langages, dans la mesure oĂč il croyait que câĂ©tait un type dâĂ©crits qui ne connaissait tout simplement pas de grammaire. Ă la diffĂ©rence de lâallemand, du latin ou du japonais, les mots chinois ne sont pas contraints par des chevilles et des flexions qui prescrivent leur position correcte dans la phrase. Et il nây pas non plus de distinction entre les noms et les verbes, de sorte quâun terme unique peut agir en mĂȘme temps comme un nom, un verbe, ou un adjectif. Ceci a conduit Fenollosa a proposer quâil y a une extrĂȘme vivacitĂ© de lâĂ©criture chinoise, et câĂ©tait avec cette qualitĂ© que Pound a tentĂ© de rivaliser dans sa poĂ©sie.

Câest Hugh Kenner qui a Ă©tabli explicitement le rapport entre lâintelligence par Fenollosa de lâĂ©criture chinoise et les textes de Pound dans sa publication de 1951, "The Poetry of Ezra Pound" â un travail qui aura certainement Ă©tĂ© connu dâAndre. Ă travers les rĂ©fĂ©rences aux essais de Pound, Kenner Ă©tablit que dans le travail symboliste du poĂšte, Pound gĂ©nĂ©ra des impressions descriptives en mettant simplement par Ă©crit sur la page des listes de renseignements concrets. En fait, Kenner suggĂšre que tout comme nous pouvons nous faire une idĂ©e des goĂ»ts dâune personne en inspectant sa collection de livres, nous pouvons aussi gagner un sens intelligible dâun poĂšme consistant simplement en une liste de morceaux de phrases dĂ©connectĂ©es, qui Ă premiĂšre vue apparaissent nâavoir aucun liens Ă©vidents.(7) Kenner appuie fortement sur le fait que Pound avait compris que la tĂąche centrale du poĂšte Ă©tait de nommer les choses justement et avec prĂ©cision. CâĂ©tait un principe quâAndre adoptera Ă©galement, et lui aussi est venu Ă croire quâ « appeler les choses par leur bon nom » Ă©tait un acte de signification fondamentale.(8)

Andre a dit une fois Ă Hollis Frampton que sa dĂ©cision de ne rĂ©duire sa poĂ©sie quâĂ des mots isolĂ©s lui Ă©tait venue Ă 3 heures du matin une nuit pendant lâhiver de 1959, alors quâil effectuait un couplage en tant que serre-freins sur le dĂ©pĂŽt de Westbound Hump du Greenville Rairoad dans le New Jersey.(9) Mais Ă nouveau il doit ĂȘtre soulignĂ© quâAndre nâĂ©tait pas le premier Ă avoir voulu dĂ©composer la poĂ©sie Ă son niveau primitif. Nous pourrions penser, par exemple, Ă William Carlos Williams pour qui la notion de construction dâun poĂšme Ă partir de mots isolĂ©s Ă©tait quelque chose que lui aussi a pris trĂšs au sĂ©rieux. Cependant des poĂštes tels que Williams sâĂ©taient toujours heurtĂ©s au problĂšme de savoir comment ils pourraient faire cela sans recourir uniquement au non poĂ©tique, ou au prosaĂŻque.(10) La perspective dâAndre, dâun autre cĂŽtĂ©, est entiĂšrement diffĂ©rente. Il a choisi trĂšs dĂ©libĂ©rĂ©ment de sâen tenir "exclusivement" au prosaĂŻque.

Le poĂšme dâAndre "500 Terms for Charles A Lindbergh" est typique de ces travaux qui sont composĂ©s en sĂ©lectionnant des mots individuels Ă partir de textes sources, et ensuite en les ordonnant sur la page selon un choix de critĂšres simples et allant de soi, qui, dans ce cas, est celui de la liste alphabĂ©tique. Quoi que lâon fasse de ce geste, la poĂ©sie conçue de cette maniĂšre nâest clairement pas comprise en tant quâacte dâ « imagination », ou mĂȘme de « crĂ©ativitĂ© ». Au lieu de ça, elle semble plutĂŽt davantage comparable aux rigueurs froides et sans passion de lâinformatique. Plus profondĂ©ment, câest une sorte de poĂ©sie qui accepte clairement et distinctement quâun poĂšme soit composĂ© de rien de plus et rien de moins que des mots, et que ce nâest pas la responsabilitĂ© du poĂšte dâinventer les mots, mais simplement de les sĂ©lectionner, et que, en fin de compte, tous les mots potentiels et disponibles sont Ă©numĂ©rĂ©s dans les dictionnaires.

Nous pourrions aussi suggĂ©rer que lâentendement par Andre de lâĂ©criture poĂ©tique en tant quâensemble de parties interchangeables et permutables, prises largement de sources prĂ©existantes, fournit une analogie trĂšs claire avec les sculptures dâAndre. AprĂšs tout, les sculptures sont aussi composĂ©es dâarrangements de particules sĂ©parĂ©es et sĂ©parables, et Andre ne commence jamais Ă travailler comme artiste avant dâavoir Ă sa disposition une sĂ©rie limitĂ©e dâunitĂ©s quâil peut ensuite rĂ©unir ensemble.

La diffusion

ArrivĂ© Ă 1965, la carriĂšre dâAndre comme sculpteur dĂ©collait lentement : câest lâannĂ©e oĂč la galerie Tibor de Nagy Ă New York a acceptĂ© de reprĂ©senter son travail, et il a eu deux expositions personnelles avec eux, avant dâintĂ©grer la galerie Dwan en 1967. Puisquâil changeait pour se concentrer sur la sculpture, il nâest peut-ĂȘtre pas Ă©tonnant que son rapport Ă sa poĂ©sie ait changĂ© aussi. En fait, Andre se mit Ă utiliser les techniques stylistiques quâil avait dĂ©veloppĂ©es dans sa poĂ©sie de façon Ă produire des Ă©noncĂ©s Ă©crits sur ses sculptures. Ces poĂšmes dâinterprĂ©tation Andre les a catĂ©gorisĂ© dĂšs lors de « planes » [plans] et un certain nombre dâentre-eux ont Ă©tĂ© publiĂ©s dans des catalogues dâexposition en guise dâĂ©noncĂ©s en prose.(11) Par exemple, dans le catalogue pour la cĂ©lĂšbre exposition de groupe, « Primary Structures » au Jewish Museum en 1966, Andre procura un "plane" de quatre strophes comme moyen dâintroduire les spectateurs Ă son art sculptural.(12) Il se compose exclusivement de noms de quatre lettres. La contribution dâAndre Ă lâexposition fut la sculpture "Lever", un travail qui consiste en une rangĂ©e unique de 137 briques rĂ©fractaires qui sâĂ©talent en long sur sol. Les visiteurs de lâexposition ont dĂ» sâattendre Ă trouver dans le catalogue un texte quelconque dâexplication, ou un exposĂ© de sa raison dâĂȘtre par Andre. Au lieu de cela il ont trouvĂ© une Ă©trange liste de mots. NĂ©anmoins il est clair quâĂ la fois les mots dans le "plane" et les briques rĂ©fractaires composant la sculpture sont disposĂ©s, unitĂ© par unitĂ©, comme de la maçonnerie. Et exactement comme il nâest fait usage dâaucun matĂ©riau de liaison pour maintenir ces briques en place, de mĂȘme les mots sont dĂ©nuĂ©s de fixatifs grammaticaux. DâĂ©vidence, le texte dâAndre nâest pas de lâexĂ©gĂšse. Ces noms ne vont pas seulement rapporter une action se dĂ©roulant autre part, mais vont, eux-mĂȘmes, effectuer lâaction.

Certainement, de trĂšs bonne heure, les critiques ont pris conscience que pour Andre le textuel et le sculptural Ă©taient des activitĂ©s qui sont de façon frappante intimement reliĂ©s, et quâil Ă©tait simplement quant Ă lui autant concernĂ© par la propriĂ©tĂ© des mots que par la qualitĂ© des matĂ©riaux. En fait, dans les interviews de la fin des annĂ©es 60, Andre a facilitĂ© souvent lui-mĂȘme la comparaison en indiquant trĂšs explicitement les rapprochements entre ses poĂšmes et les sculptures. CâĂ©tait, en dâautres mots, la rĂ©putation de lâartiste comme sculpteur qui a provoquĂ© lâintĂ©rĂȘt public pour sa poĂ©sie, et Ă ce jour ses poĂšmes nâont reçu que peu ou pas de considĂ©ration venant de parties qui ne sont pas dĂ©jĂ habituĂ©es au statut dâartiste dâAndre.

La question, cependant, Ă©tait de quelle maniĂšre les poĂšmes dâAndre pourraient ĂȘtre le mieux prĂ©sentĂ©s au sein dâun contexte artistique ? Il semble honnĂȘte de suggĂ©rer que mĂȘme Ă partir dâun stade prĂ©coce, Andre nâĂ©tait pas satisfait de voir ses travaux Ă base de textes reproduits dans des livres avec comme seule intervention une police de caractĂšre gĂ©nĂ©rique sĂ©lectionnĂ©e par lâĂ©diteur. Quâils soient prĂ©sentĂ©s de la sorte revient Ă saper les qualitĂ©s visuelles clĂ© de ses travaux, principalement parce que cela nĂ©glige le rĂŽle significatif tenu par la machine Ă Ă©crire dans leur production. Avant tout, câest la marque dâimpression de la lettre encrĂ©e sur la page qui a toujours Ă©tĂ© si importante pour Andre, et puisque le papier imprimĂ© en relief par le texte est ce qui compte pour lui, la reproductibilitĂ© et la diffusion nâont tout bonnement jamais eu beaucoup dâimportance pour lui. Donc, aux alentours de 1967, Andre a commencĂ© Ă exposer et Ă vendre des manuscrits individuels de ses poĂšmes comme Ćuvres Ă part entiĂšre. Plus tard, des feuilles de papier tapĂ©es Ă la machine et des copies carbones ont Ă©tĂ© encadrĂ©es sur les murs de la mĂȘme façon quâauraient pu lâĂȘtre des estampes ou des dessins.

La photocopie

En 1968, Andre collabora, avec dix autres artistes Ă la production dâun catalogue auquel on fait souvent rĂ©fĂ©rence aujourdâhui en tant que "The Xerox Book". Les artistes, qui comprenaient Robert Barry, Daniel Buren, Jan Dibbets, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, N E Thing Co., Robert Smithson et Lawrence Weiner, sâĂ©taient tous vus allouer par leur Ă©diteur, Seth Siegelaub, vingt cinq pages chacun avec lesquelles explorer les qualitĂ©s de la reproduction par photocopie.(13) Pour lâĂ©poque, le livre Ă©tait produit en sĂ©rie â au total mille exemplaires ont Ă©tĂ© publiĂ©s. Mais ce nâĂ©tait pas lâobjectif principal, le but Ă©tant dâinviter les artistes Ă explorer les qualitĂ©s de cette technologie relativement nouvelle. La contribution dâAndre a Ă©tĂ© de laisser tomber vingt cinq petits morceaux carrĂ©s de carton sur lâĂ©cran du copieur, un Ă la fois. Chaque fois quâil laissait tomber un des carrĂ©s, il fasait une photocopie de sa dispostion. Le rĂ©sultat est un ensemble de pages qui enregistre le processus de sa propre fabrication â un thĂšme quâAndre explorait aussi dans ses sculptures Ă lâĂ©poque.(14)

LâannĂ©e suivante, Siegelaub a fait la dĂ©marche de proposer Ă Andre dâĂȘtre son propre Ă©diteur dâune anthologie de ses poĂšmes, qui pourrait ĂȘtre produite en conjonction avec la Dwan Gallery. Une nouvelle fois il sera fait usage de la technologie de la photocopieuse. Lâavantage dâutiliser le photocopieur aura Ă©tĂ© de prĂ©server les caractĂ©ristiques visuelles des poĂšmes, au moins jusquâĂ un certain degrĂ©. Andre a divisĂ© sa poĂ©sie en sept sections, dont chacune se composait dâun volume en propre. Il sâagissait de : "Passport", (1960), "Shape and Structure", (1960-65), "A Theory of Poetry", (1960-65), "One Hundred Sonnets", (1963), "America Drill", (1963), "Three Operas", (1964) and "Lyrics and Odes" (1969).Les sept volumes rĂ©sultants Ă©taient rĂ©unis dans des classeurs plastiques noirs Ă anneaux, et au total seulement trente-six Ă©ditions ont Ă©tĂ© rĂ©alisĂ©es. Il semble honnĂšte de suggĂ©rer quâAndre nâĂ©tait pas particuliĂšrement satisfait du rĂ©sultat. Certaines pages des poĂšmes Ă©taient mal dĂ©coupĂ©es, et la qualitĂ© de reproduction est, dans certain cas, relativement faible.

Cependant, ces expĂ©riences avec la photocopie semblent avoir retenu l'intĂ©rĂȘt d'Andre, et lors des deux dĂ©cennies Ă venir il sâest mis Ă faire des expĂ©riences avec les photocopies en tant que moyen de faire circuler sa poĂ©sie. Ce qui lâa intĂ©ressĂ© nâĂ©tait pas la possibilitĂ© de la reproduction potentiellement sans limites, il faut insister lĂ -dessus, mais les caractĂ©ristiques distinctives du texte photocopiĂ© â la façon dont des blocs dâombres plus sombres peuvent Ă©merger, ou le degrĂ© jusquâoĂč le texte sâestompe, et ainsi de suite. De retour au milieu des annĂ©es 50, Andre avait un temps travaillĂ© comme garçon de bureau au Boston Gear Works dans sa ville natale de Quincy, et une de ses tĂąches Ă©tait de manĆuvrer une machine Ă copier primitive qui dupliquait des contre-calques de dessins industriels. De fait on pourrait suggĂ©rer que lâintĂ©rĂȘt dâAndre pour les Ă©tranges distorsions et les effets de cette forme de technologie dâimpression a Ă©tĂ© provoquĂ© en partie par ces expĂ©riences prĂ©coces. Au dĂ©but des annĂ©es 1970, Andre a eu accĂšs Ă une machine Ă photocopier couleur, qui, Ă lâĂ©poque, Ă©tait une technologie toute nouvelle et encore inexplorĂ©e. Il a Ă©tĂ© particuliĂšrement sĂ©duit par les Ă©tranges couleurs acides quâelle gĂ©nĂ©rait, et il a fait un nombre limitĂ© de copies de "Passport". Bien que "Passport" soit souvent associĂ© aux poĂšmes, câest en rĂ©alitĂ© un album fait lui-mĂȘme, constituĂ© de divers dessins, tableaux, timbres, documents et coupures de journaux qui lâont intĂ©ressĂ© lorsquâil Ă©tait jeune artiste Ă New York. Dans ces photocopies couleur, cependant, les pages apparaissent entiĂšrement diffĂ©rentes, et le rĂ©sultat est un ensemble extraordinaire de reproductions, pleines de couleurs dĂ©sagrĂ©ables qui jurent entre elles et dâeffets visuels singuliers.

Au cours des annĂ©es, Andre a produit des ensemble trĂšs limitĂ©s de photocopies de quelques-uns de ses poĂšmes, et Ă ce jour cela reste le moyen principal par lequel les poĂšmes sont diffusĂ©s. Bien que les copies d'Andre ne soient pas exactement des Ă©ditions limitĂ©es, chaque reproduction porte cependant au dos un numĂ©ro d'index. De plus, puisque la vaste majoritĂ© des manuscrits originaux est maintenant dans les mains de collections publiques de musĂ©es, ou de collections privĂ©es, il est peu probable quâaucune nouvelle copie ne soit gĂ©nĂ©rĂ©e Ă partir des originaux.

Andre a toujours considĂ©rĂ© chaque copie comme unique. En tant que notion, cela peut nous frapper comme potentiellement contradictoire, dans la mesure oĂč nous pourrions bien penser que lâidĂ©e mĂȘme de photocopie implique la possibilitĂ© de faire des Ă©preuves sur papier Ă bon marchĂ© et (au moins dans la possibilitĂ©) sans limites. Cependant en un certain sens, Andre est un artiste qui se sert trĂšs souvent de matĂ©riaux et de ressources qui "semblent" pouvoir ĂȘtre rĂ©pliquĂ©s Ă lâinfini, mais en fait ne le sont pas. Pensez, par exemple, Ă ses piĂšces des annĂ©es 60 constituĂ©es de briques produites industriellement â telles que "Lever", de 1966. Une rangĂ©e de briques sâĂ©talant en long sur le sol a lâair de suggĂ©rer si clairement que la ligne pourrait ĂȘtre Ă©tendue indĂ©finiment. Pourtant Andre en utilisa un nombre limitĂ© et trĂšs spĂ©cifique â 137 â et si lâune quelconque de ces briques venait Ă ĂȘtre enlevĂ©e, ou de nouvelles Ă ĂȘtre ajoutĂ©es, aux yeux dâAndre le travail serait dĂ©truit. En dâautres mots, tandis que lâart dâAndre embrasse trĂšs souvent lâidĂ©e de la possibilitĂ© de rĂ©pĂ©tition sĂ©rielle sans fin, il contient aussi une injonction trĂšs puissante allant contre cette logique. La mĂȘme chose pourrait ĂȘtre dite des poĂšmes photocopiĂ©s dâAndre.

Notes:

(1) Hollis Frampton, Lettre Ă Reno Odlin, 11 mars 1964, dans "Hollis Frampton Letters", Second Edition, Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre, 2002, p. 119.

(2) Carl Andre dans une interview avec Lynda Morris, p. 14; réimprimé dans "Cuts: Texts, 1959-2004", éd. par James Meyer (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), p. 212.

(3) Paul Cummings, âTaped Interview with Carl Andreâ, 1973; rĂ©imprimĂ© dans "Cuts: Texts, 1959-2004", p. 212.

(4) Robert Smithson, âA Museum of Language in the Vicinity of Artâ [1968], dans "Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings", Ă©d. par Jack Flam (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 1996), pp. 79-80

(5) Michel Butor, "Mobile: Ătude pour une reprĂ©sentation des Ătats-Unis", Gallimard, 1962.

(6) Carl Andre, dans Carl Andre et Hollis Frampton,

"Twelve Dialogues: 1962-63", The Press of the Nova Scotia School of Art

and Design and New York University Press, Halifax, 1980, p. 37.

(7) Hugh Kenner, "The Poetry of Ezra Pound", p. 84.

(8) Voir Phyllis Tuchman, âAn Interview with Carl Andreâ, "Artforum", vol. 8, no. 10 (Juin 1970), pp. 55-61, p. 60.

(9) Carl Andre, dans Carl Andre et Hollis Frampton, "Twelve Dialogues: 1962-63", p. 77.

(10) William Carlos Williams articule peut-ĂȘtre cette admiration pour les mots uniques dans ses essais sur Marianne Moore et Gertrude Stein dans "Imaginations" (London: McGibbon & Kee, 1970).

(11)Voir James Meyer, âCarl Andre: Writerâ, dans "Cuts: Texts, 1959-2004", p. 3.

(12) Voir lâintervention de Carl Andre dans Kynaston McShine, "Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors", catalogue dâexposition, New York, Jewish Museum, 1966.

(13) "Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Daniel Buren, Jan Dibbets, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Richard Long, N E Thing Co. Ltd , Robert Smithson, Lawrence Weiner", Catalogue dâexposition, Ă©d. par Seth Siegelaub, 1969.

(14) Pour une discussion de la contribution dâAndre Ă "The Xerox Book", voir Alexander Alberro, "Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity" (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003), pp. 136-140.

Biographie

ALISTAIR RIDER enseigne Ă la School of Art History de lâUniversity of St Andrews en Ăcosse, et donne des confĂ©rences sur lâart amĂ©ricain dâaprĂšs-guerre. Il est en train dâĂ©crire un livre sur les poĂšmes et les sculptures de Carl Andre qui sera publiĂ© lâan prochain par Phaidon. Actuellement il consacre ses recherches Ă lâimpact de la conscience Ă©cologique sur les artistes et les critiques dâart Ă la fin des annĂ©es 60, et il projette une exploration Ă plusieurs niveaux de lâemploi des matĂ©riaux par les artistes pendant les annĂ©es 1960 et 70.

Ce texte © Alistair Rider, mars 2009.

Traduction © Arnaud Lefebvre, avril 2009.

|

Exhibit Images

CARL ANDRE "POEMS"

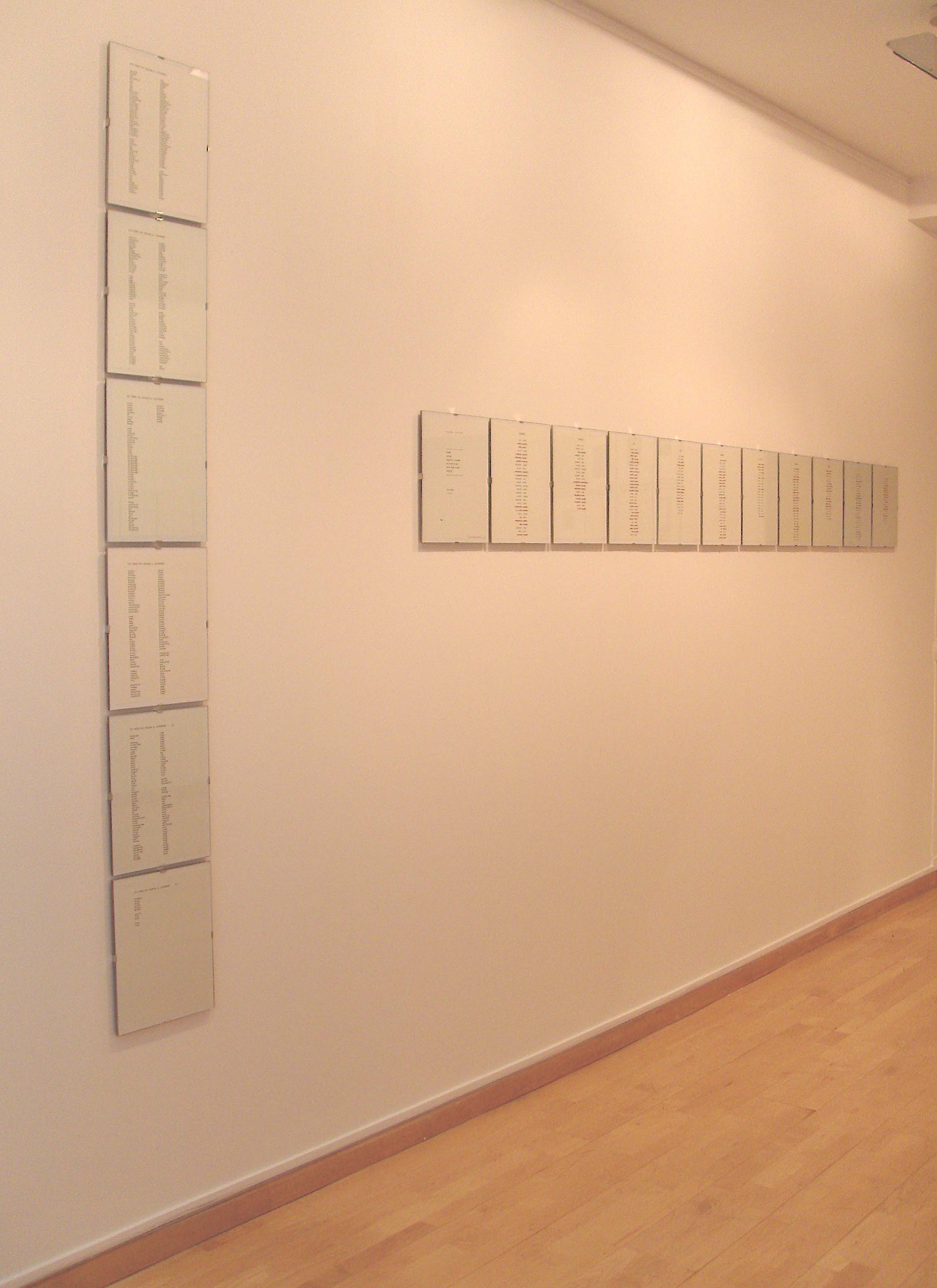

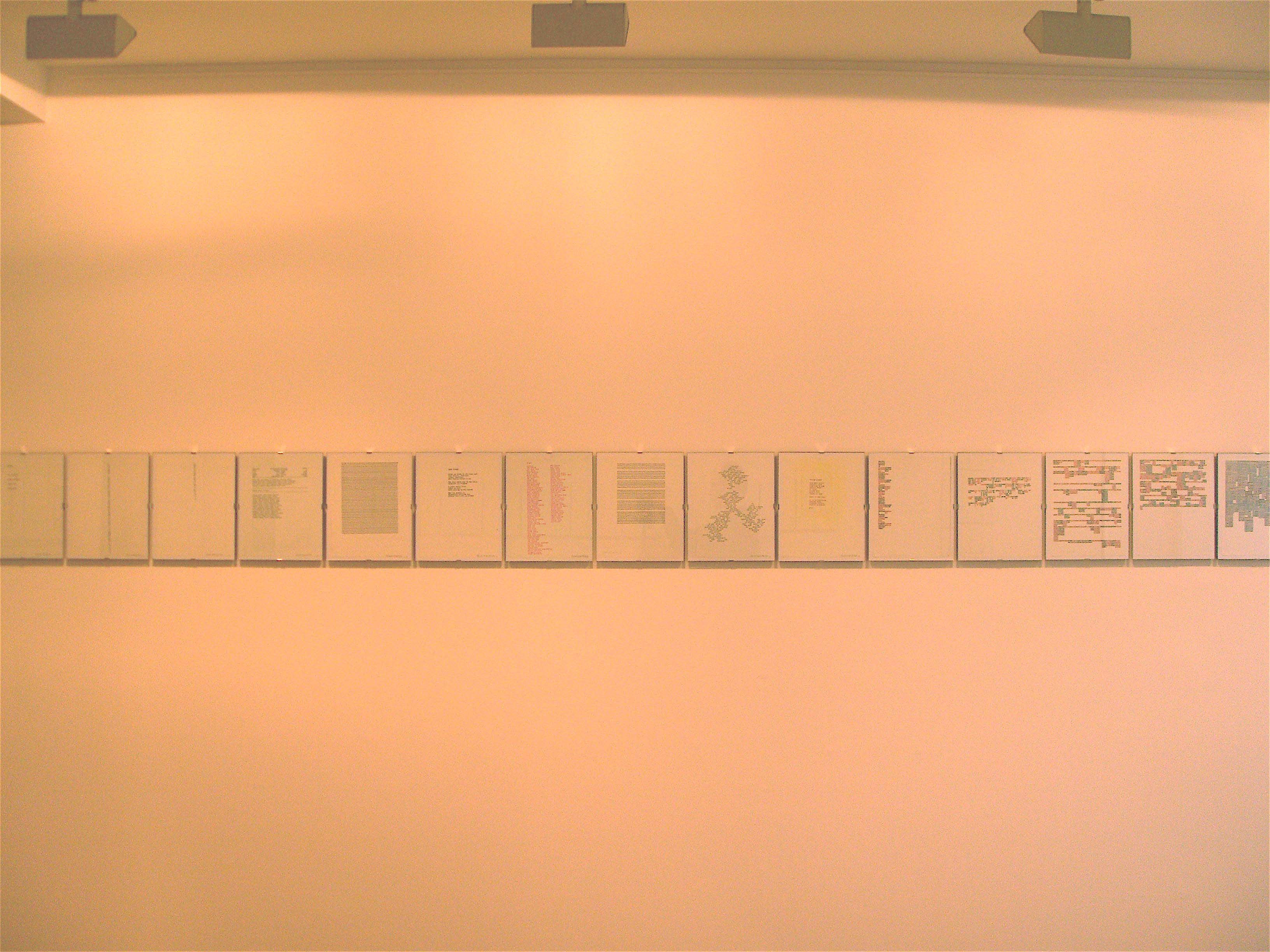

Vue d'ensemble

2009 © Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre

CARL ANDRE: "500 TERMS FOR CHARLES A LINDBERGH"; "THREE SACHEM"

2009 © Carl Andre

CARL ANDRE "500 TERMS FOR CHARLES A LINDBERGH", 1968, 6 pages, signées, photocopie, 6 x (28x21,5 cm)

2009 © Carl Andre

CARL ANDRE "THREE SACHEM", 1963, 11 pages, page de titre signée, photocopie, 11 x (28x21,5 cm)

2009 © Carl Andre

CARL ANDRE "PASSPORT", 1960, sélection de 12 pages, signées, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm

2009 © Carl Andre

CARL ANDRE, 15 Poems.

2009 © Carl Andre

CARL ANDRE: "SALUTE", 1958/1963, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"m", 1958/1966, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"t", 1958/1966, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"HATHAWAY MIDDLETOWN ENGLISH",1959, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"wwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww", 1960/1965, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"SAND STREET", 1959/1960, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"VISAS",1960/1962, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"pppppppppppppppppppppppppppp", 1962, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"Intimate",1961/1963, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"MYRTLE AVENUE", 1963/1964, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"YUCATAN, POLITIC", 1972, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"YUCATAN, SEARCH JOURNEYRUINEDLOSE", 1972, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"YUCATAN, DEPARTUOUTRANCHOOF", 1972, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"YUCATAN, ANARCOTHERBURICHLY", 1972, signé, photocopie, 28x21,5 cm;

"YUCATAN, JJJJJJJJJJJJJJEEEEEE", 1972, signé, photocopie, 28 x 21,5 cm.

2009 © Carl Andre |