|

|

|

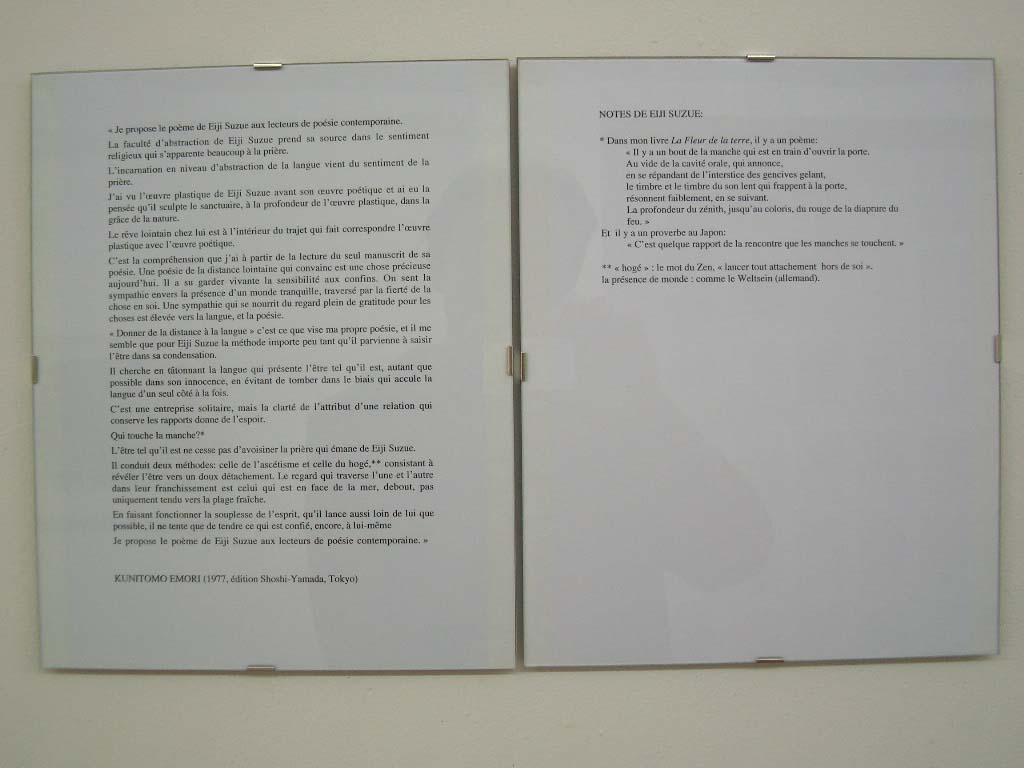

ALTER CARNOL, ROSEMARIE CASTORO, KUNITOMO EMORI, DAVID GORDON, ROBERT HUOT, CAROL KINNE, MARTINA KLEIN, JUDITH NELSON, PAUL NELSON, EIJI SUZUE: "Une Journée dans la vie d'un galeriste" 1O mai - 30 juin 2007 jeudi 28 juin 2007 à 19h: lecture par Arnaud Lefebvre Thursday June 28, 2007, at 7 pm: reading by Arnaud Lefebvre ARNAUD LEFEBVRE UNE JOURNEE DANS LA VIE D’UN GALERISTE LECTURE 28.6.2007 A 19H C’est la seconde fois qu’est exposé à la galerie le poème de Rosemarie Castoro « A Day in the Life of a Conscientious Objector » (Une Journée dans la vie d’un objecteur de conscience), réalisé entre le 23 février et le 26 mars 1969. Rosemarie en avait fait une très belle lecture à la galerie en 1997, et elle vient d’en réaliser une nouvelle à Trancoso, au Portugal. Dans un e-mail à la galerie, Rosemarie Castoro a indiqué à propos de son poème : « J’ai trouvé les heures de 4 à 6 de l’après-midi un temps tout particulièrement inconscient, consacré aux rêveries tranquilles. J’ai pensé devenir active, plutôt que de m’assoupir. J’ai utilisé différentes couleurs de feutres pour changer les voix et pensées à l’intérieur de la structure du bloc d’exercices calligraphiques, restant d’un cours que j’avais pris au Pratt Institute. Le cours était pour les droitiers, pour apprendre l’écriture italique « Chancery ». Je suis gauchère. A chaque deux heures quotidiennes je m’asseyais tranquillement avec mes pensées, témoignais d’une heure en tant que d’une page. Je souhaite capturer le moment fugitif et le rendre permanent, dans ce cas, le temps. Dans d’autres « travaux de mots », j’ai utilisé un « chronomètre » pour m’observer moi-même et prendre le temps de mes activités. “A Day in the Life of a Conscientious Objector” fait partie de mes travaux de structure de temps, me servant de l’horloge comme d’un véhicule pour transporter mes pensées. » La poésie de Rosemarie Castoro occupe une place à part dans son travail. Je pense qu’elle la relie à son travail d’écriture, plutôt qu’elle ne la voit comme une activité autonome. Le poème est issu de son écriture et en représente une forme aboutie. Cependant sa production écrite est un domaine important de son oeuvre. Il m’a toujours semblé que son écriture prenait une place dans l’espace des mots qui évoquait celle que sa sculpture occupait dans l’espace du corps. J’ai eu plusieurs fois la sensation qu’une même ligne se dessinait dans les deux et qu’on y retrouvait ces mêmes caractères de force et de souplesse, de nervosité et de rythme, de sûreté et de rapidité qui sont présents dans ses Flashers (exhibitionnistes), ses Sarcophagi (sarcophages), et également dans ses dessins aveugles de spectatrice d’opéra ou de ballet. Les mots chez Rosemarie Castoro ne sont pas des objets neutres et anonymes, ils sont chargés d’une efficacité et d’un grand pouvoir de jeu. De même il est étonnant de voir la maîtrise qu’a Rosemarie à intégrer, plutôt qu’à exclure, dans son travail la personne privée pour en faire un matériau qui vienne nourrir son art. Le contexte des Etats-Unis de 1969, avec la tragédie de la guerre du Vietnam, et celui de New York avec l’extraordinaire effervescence artistique qui y régnait et dont Rosemarie Castoro était une actrice à part entière, sont inscrits en filigrane dans son poème, comme sont inscrits dans les peintures rupestres de Lascaux ou d’Altamira les manifestations d’une des premières facultés de représentation et d’abstraction de l’espèce humaine. The survival of the beautiful Oriole’s throat hearts the artist: Brancusi, Bach with beauty interlock. DAVID GORDON Appelons A ma voix, et B celle de David Gordon : A : Le court poème de David Gordon a été écrit spécialement pour l’exposition. Ses 5 petites lignes parlent de beauté, de chant du loriot, d’art, de Brancusi et de Bach. La ligne centrale « hearts the artist » semble être le pivot du poème. De la gorge du loriot nous passons à l’art de Brancusi et de Bach. Prononcez pour vous-même « oriole’s throat » et vous y retrouverez une consistance du chant du loriot. B : comme un exemple de ce qu’Ezra Pound a appelé « conduite de voyelle », en ce que le « o » de « oriole » dessine les qualités musicales du mot « oriole » dans ceux de « throat », une assonance que Pound a appris de Sappho, Dante et Arnautz Daniel. Cette même assonance peut être vue dans « hearts the artist » tandis que les notes tenues des « o » et « a » joignent les deux membres de phrases. A :« Hearten » comme verbe, réunit en lui le principe actif du poème. En même temps, il est résonance de ce qui se passe avant et après lui. Le mot « beauty » à la fin du poème glisse sur la coda du verbe, dans les frappés en pincée de corde des « b » et des « k » qui l’introduisent et le concluent: « Brancusi, Bach with beauty interlock. » B : ce qui est renforcé par les rythmes internes et les allitérations terminales de « Bach » avec « lock », et avec le « u » dans « beauty » avec le « u » dans « Brancusi », et avec le « b » comme allitérations initiales dans « Bach » et « Brancusi », ce qui infuse l’ensemble du poème d’un sens dans lequel Brancusi continue dans la tradition comme maître-artiste avec Bach. A : La poésie de David Gordon a été présentée à plusieurs reprises à la galerie. Les dix parties de son Long Poème VOYAGE sont aujourd’hui complètes. C’est une des grandes entreprises poétiques de notre époque. VOYAGE est pionnier par de multiples aspects dont le propre domaine d’investigation du poème, le traitement de chacune des voix qui compose le poème, et l’orientation donnée au poème qui suit un plan d’ensemble indiquant la direction dans laquelle l’œuvre progresse. Kunitomo Emori a écrit le texte présenté ici pour le recueil de poèmes d’Eiji Suzue : “La Fleur de la Terre” (1997). Ce texte de Kunitomo Emori est précieux car il nous dit avec une grande clarté d’où vient la poésie d’Eiji Suzue, et le chemin qu’empruntent ses mots pour parvenir jusqu’au lecteur. Kunitomo Emori nous en parle en tant que poète lui-même : une notice biographique d’un recueil récent nous dit qu’il « est né près de Tokyo en 1933, a été un chef de file de la première génération des poètes d’après-guerre. Sa poésie expérimentale quoique infailliblement lyrique est parue en plusieurs volumes publiés. » C’est une expérience qui apprend beaucoup de participer à la correction d’un poème en français par Eiji Suzue. On résiste, on se défend, on semble ne plus y reconnaître sa propre langue... Elle est insufflée d’un esprit qui lui donne une physionomie que je ne lui connais pas.... Mais cependant quelque chose dans la langue lui permet de fonctionner, et progressivement, mot après mot, le poème retombe sur ses pieds. On expérimente dans l’art d’Eiji Suzue une sorte de résultante, qui serait comme une réalité en suspens provenant de la réaction de deux mouvements différents qui s’équilibreraient au fur et à mesure de leur avancée. La question que pose Kunitomo Emori dans son texte : « Qui touche la manche ?» semble inclure dans un même élan le poème et son lecteur, chacun jouant son rôle de partenaire. Les mots en français d’Eiji Suzue sont plus qu’une traduction, ils sont une langue qui agit sur une autre et qui nous entraîne dans son courant. ma lumière néanmoins beauté succulente chemine péniblement son jardin joue dans notre pluie transpire dans un moment essentiel Ce « Poème de frigidaire » de Carol Kinne est la traduction d’un des cinq présentés ici. Dans une lettre à la galerie, Robert Huot raconte : « Il y a quelques années Carol a eu un paquet de mots aimantés qu’elle a collé sur son frigidaire. Les mots étaient arbitrairement « choisis » par le fabriquant (par nombre ou poids — qui sait ?) De temps en temps elle les change de place pour former de nouveaux « poèmes ». » — Ne trouvez-vous pas avec moi que leur vent de liberté, d’humour et d’intelligence s’imposait à l’exposition? L’édition “Während 34 Tagen” (Pendant 34 jours) de Walter Janßen et Martina Klein est une édition qui se feuillette. A l’issue de leur exposition en commun à la galerie en 2004, ils ont voulu marquer le temps de cet intense dialogue artistique de leur très belle exposition. Ils ont combiné les images de l’exposition avec le temps du journal. Leur choix s’est porté sur le journal le plus largement représentatif de la presse française pour deux artistes allemands, Le Monde. La période de l’exposition a été couverte par 34 parutions du quotidien. Entre les pages de chaque journal, ils ont inséré les mêmes 8 photos de l’exposition. Leur intervention semble presque faire partie du journal original, pourtant elle crée une surprise et suscite un nombre d’interrogations. Par exemple : Est-ce que la mobilité de la page que je tiens en main est de même nature que le détachement de la peinture rouge de Martina Klein? Est-ce que l’information de la page que je viens de tourner s’inscrit dans ma mémoire comme le cylindre d’aluminium a inscrit sa trace sur le plâtre du mur de la galerie? Comment est-ce que ma mémoire et mon attention se renouvèlent à chaque nouvelle page ? Est-ce qu’un travail d’art fait partie du monde dans lequel nous vivons ou est-ce qu’il est quelque chose à part ? Est-ce qu’un travail d’art à côté d’un autre travail d’art raconte quelque chose? Qu’est-ce qu’ils ont à dire ? Est-ce qu’une œuvre d’art s’exprime toute seule ou a-t-elle besoin d’un apprentissage de l’œil qui la regarde? Quelle est la question d’actualité d’une œuvre d’art ? Qu’est-ce que la peinture veut dire aujourd’hui ? Et la sculpture ? Est-ce que l’art appartient à une géographie ? Une économie ? Une politique ? Quel rapport cela a-t-il avec moi ? Dans le cadre de cette exposition, cette édition prend une valeur particulière, comme un appel à l’art ici et maintenant. L’exemplaire qui est exposé est le n° 5/34, correspondant au journal du samedi 23 octobre 2004. En réponse à ce texte que je leur ai envoyé, Martina Klein et Walter Janßen ont écrit : « l’édition “Während 34 Tagen” est faite par Walter Janßen et Martina Klein. Si tu as envie d’en parler, c’est ta décision. » Les textes en anglais de Robert Huot sont accompagnés des traductions françaises qui ont été faites depuis la première présentation du travail de Robert Huot à la galerie, en octobre 2005. Il est difficile de résumer l’ensemble de ces textes car ils contiennent beaucoup d’informations et abordent de multiples aspects de son travail. Mais il sont tous centrés sur l’art et la vie de Robert Huot et vont directement au vif du sujet. Ils ont été écrits pour l’essentiel par Robert Huot et par Scot MacDonald, historien et critique de cinéma expérimental. Robert Huot a fait de la peinture, en comptant parmi les premiers artistes de l’art minimal, puis des films, des performances, de la musique, des installations. La variété des médias qu’il emploie et la diversité de ses investigations et langages artistiques peuvent dérouter le spectateur. Il a abordé aussi bien l’abstraction la plus radicale que la figuration la plus psychologique, la disparition du sujet que la narration du journal intime, la modernité la plus avancée que l’archaïsme le plus enfoui, l’art le plus personnel que l’art le plus politiquement engagé, le geste de la main que le jeu de la machine, l’ordre que le chaos. Robert Huot semble tout accueillir dans son art et vouloir se dérober à la saisie unique. Mais cependant son travail est là devant nos yeux, avec un contour net et précis et une forme sans ambiguïté. Et il est étonnant de voir que cette multiplicité définit dans le temps une forte cohérence, comme un nouveau travail qui apporterait des perspectives nouvelles et inattendues sur le reste des travaux précédents. Cela m’a frappé lorsque Robert Huot est venu à Paris, qu’il dise se considérer finalement comme peintre, et en insistant que sa peinture n’est pas de la peinture de chevalet. Ces textes couvrent un large itinéraire de la production de Robert Huot. J’ai eu beaucoup de plaisir à les traduire car ils font entrer dans la vie du contexte qui a démarré à la fin des années 50 aux Etats-Unis, et qui est une très grande époque artistique. Voici un extrait de L’Art du Contexte. C’est Robert Huot qui parle : « D’abord je dois ouvrir plus grand la fenêtre du temps. Quand je pense aux problèmes de l’art je dois revenir aux années 50 et aux jours de la 10e rue à New York City. J’étais un jeune homme qui aimait éperdument la vie d’artiste, traînant avec les artistes de la 10e rue — faisant la fermeture du Cedar Bar — discutant toute la nuit d’art et de politique — étant un rebelle et pourtant prenant part à une cause (ce que je vois maintenant comme une industrie en expansion) ce que je voyais alors comme une façon de vivre enivrante — bohémienne — radicale — très différente de l’asservissement à six jours par semaine de mon père. L’École de New York était à son apogée et j’en étais une petite partie. J’allais à chaque exposition, chaque vernissage, et chaque réception. Bientôt je connaissais tout le monde (le monde de l’art était plus petit alors). Je travaillais dans mon atelier 14 heures par jour — faisais plus de peintures que n’importe qui d’autre de ma connaissance — occupant un travail à plein temps. Je ne dormais pas beaucoup — ne faisait que travailler et sortir. Pendant environ un mois chaque année je m’écroulais, puis me remettais sur pied pour la prochaine ligne droite d’art et de folie. C’était formidable — j’étais jeune — je n’avais à m’inquiéter de personne que de moi et je ne m’en inquiétais pas beaucoup — j’étais un artiste — point. Donc j’entrais dans ma vie d’art avec une sorte de ferveur religieuse (bien que très séculaire). Je passais rapidement « d’apprentis » à « compagnon » et commençais en même temps que beaucoup d’autres, à développer un style pour rivaliser avec l’expressionnisme abstrait — ce qui devait bientôt être appelé « art minimal ». L’art minimal de mon point de vue était un style d’efficacité — direct — couleur, forme, taille, emplacement, surface et lumière— ce que vous voyez est ce que vous obtenez. Une réaction à « l’écriture automatique », la nature idiosyncrasique du style dominant alors de l’expressionnime abstrait. Nous espérions présenter la réalité des éléments de l’art comme un langage qui parlerait directement au spectateur. Cela n’était pas des idées nouvelles, mais elles semblaient fraîches et nécessaires dans le bourbier apparent du moment. » C’est peu à peu que la poésie de Paul Nelson a trouvé sa place dans la galerie. La « prise de conscience », d’une certaine façon, c’est au cours d’un travail de traduction de sa poésie. Je me suis dit que ses mots tenaient dans la mémoire, tout comme certains tableaux tiennent sur le mur... Il me paraît que sa poésie ne recherche pas le spectaculaire. Elle dit de la manière la plus simple et la plus directe quelque chose qui a lieu, quelque chose qui existe et elle le dit avec la réalité même de la chose. Peut-être pourrait-on parler d’un poème-objet en tant que l’aboutissement d’un énorme travail qui fait de la précision du mot employé l’équivalent exact de la réalité qu’il traduit. Et il me semble que sa poésie trouve sa place sur le mur, non pas par rapport à un effet visuel qui proviendrait de la composition du poème, mais parce que tout le poème est lui-même plastique, il est une forme unie qui se meut dans l’espace et le temps. SCARP de Judith Nelson combine des matériaux naturels très divers : impression de poussière rouge de carapace sur papier fait à la main, cosses de Haole koa, cosses de haleconia, écailles de pin norfolk. Voici ce que dit Judith Nelson dans un e-mail à la galerie : « La « poussière rouge » se réfère à l’encre que je réalise en broyant de la terre locale, à haute teneur en fer, et ensuite en l’imprimant sur mes papiers faits main. Le « bloc » d’impression est soit la large cosse d’un poinciane royal ou la carapace séchée d’une langouste de Hawaï. Les cosses de « Haole koa » et de pin norfolk proviennent d’arbres. Le haleconia est une plante à larges feuilles qui pousse juste à l’extérieur de notre porte arrière. » Et sur une question plus générale, Judith Nelson ajoute : « Mon art n’a pas en vue la controverse ni d’être définitif. Il embrasse mes questions et mes explorations, avec une implication vers l’ouverture à la façon dont ma réponse à un endroit spécifique est partagée avec d’autres, et la leur. » SCARP de Judith Nelson a été la première à trouver sa place dans l’accrochage de cette exposition. Elle a pour ainsi dire donné la tonalité, ou la basse de l’exposition. Elle offre aux mots qui précèdent un autre mode de relation, comme un relâchement de leur poids, et comme un point de rencontre de ce que leurs nombreuses traces s’efforcent de laisser dans le sol, les réunit, place l’air, allège leurs pieds et leur ouvre la piste. Voici deux réactions de Paul et Judith Nelson à ce que j’ai écrit sur leur travail : Paul Nelson : «Ton appréciation soigneuse et incisive de mes poèmes, sans tenir compte des traductions bien faites, me trouvent impressionné par mon propre travail … rarement mon sentiment habituel. » Et Judith Nelson : « Je suis contente des métaphores pour mon travail : la musique et le mouvement. C’est bien ça, avec le mètre et les espaces pour l’œil pour traverser dans ma pièce. » Merci à vous. ARNAUD LEFEBVRE A DAY IN THE LIFE OF A GALLERIST READING 06.28.2007 AT 7PM It is the second time that is shown at the gallery Rosemarie Castoro’s poem “A Day in the Life of a Conscientious Objector”, made between February 23 and March 26, 1969. Rosemarie did a very beautiful reading of it in the gallery in 1997, and she just did a new one at Transcoso, Portugal. In an e-mail to the gallery, Rosemarie Castoro told about her poem : “I found the hours of 4:00 PM - 6:00PM a most unconscious time, giving to quiet dreaming. I thought to become active, instead of taking a nap. I used the different colors of the pens to change voices and thoughts within the grid structure of the calligraphic practice pad left over from a class I took at Pratt Institute. The class was for right handed people, to learn the italic “Chancery” script. I am left-handed. Each of the daily two hours I sat quietly with my thoughts, evidenced one hour as one page. I wish to capture the fleeting moment and make it permanent, in this case, time. In other “word works”, I used a “stop watch” to watch myself and time my activities. A Day in the Life of a Conscientious Objector is part of my time structure works, using the clock as a vehicle to carry my thoughts.” Rosemarie Castoro’s poetry holds a special place in her work. I think she connects it to her writing work, rather than sees it as an autonomous activity. The poem comes from her writings and represents an achieved form of them. However her written production is an important domain of her work at large. It always seemed to me that her writing holds a place in the space of words which evoked the place her sculpture holds in the space of the body. Several time I had feeling that a same line was drawn into both, and that one found in them the same characters of strength and suppleness, of nervosity and rhythm, of sureness and rapidity that are present in her Flashers, Sarcophagi, and also in her blind spectator drawings of opera and ballet. Words at Rosemarie’s are not neutral and anonymous objects, they are loaded with efficiency and a great playing power. Likewise it is astonishing to see Rosemarie’s mastery to integrate, rather than exclude, in her work the private person, to make a material that comes to nourish her art. The context of the US in 1969, with the tragedy of the Viet Nam war, and the one of New York with the extraordinary artistic effervescence which prevailed and of whom Rosemarie Castoro was a full part actor, are water-marked in her poem, as are inscribed in the cave paintings of Lascaux and Altamira the manifestation of one of the first representing and abstracting faculty of the human species. The survival of the beautiful Oriole’s throat hearts the artist: Brancusi, Bach with beauty interlock. DAVID GORDON Let’s call A my voice, and B David Gordon’s : A : The short poem by David Gordon was written specially for the exhibition. Its 5 short lines speak of beauty, oriole’s song, art, Brancusi and Bach. The central line “hearts the artist” seems to be the pivot of the poem. From the throat of the oriole we pass to the art of Brancusi and Bach. Pronounce for yourself “oriole’s throat” and you will find a consistency of the oriole’s song. B: as an example of what Ezra Pound called “vowel-leading‚ in that the “o” of the “oriole” draws the musical qualities of the word “oriole” into those of “throat”‚ an assonance that Pound learned from Sappho, Dante, and Arnautz Daniel. This same assonance may be seen in “hearts the artist” as the sustained notes of “o” and “a” join the two phrases. A :“Hearten” as a verb, gathers in itself the active principle of the poem. At the same time, it is a resonance of what happens before and after it.. The word “beauty” at the end of the poem glides on the coda of the verb, in the plucked beats of the “b” and “k” which introduce and conclude it : “Brancusi, Bach with beauty interlock.” B : which is reinforced by the inner rhymes and terminal alliteration of “Bach” with “lock”; and with the “u” in “beauty” with the “u” in Brancusi and with the “b” as initial alliterations in “Bach” and “Brancusi”‚ which infuses the whole poem with the sense in which Brancusi continues in the tradition as master artist with Bach. A : David Gordon’s poetry was presented several times at the gallery. The ten parts of his Long Poem “Voyage” are now completed. It is one of the great poetical undertakings of our time. “Voyage” is pioneer by multpile aspects of which the own investigative domain of his poem, the treatment of each of the voices which compose the poem, and the orientation given to the poem which follows an overall plan indicating the direction in which the work progresses. Kunitomo Emori wrote the text exhibited here for the collection of poems by Eiji Suzue : “The Flower of the Earth” (1997). This text by Kunitomo Emori is precious as it tells us with a great clarity where Eiji Suzue’s poetry comes from, and the way his words make use of to arrive to the reader. Kunitomo Emori says it to us as a poet himself : a biographical note of a recent collection of his poems tells us he was “born near Tokyo in 1933, has been a leading light of Japan’s first generation of postwar poets. His experimental yet unfailingly lyrical poetry has appeared in several published volumes.” It is an experience which teaches a great deal to participate in the correction of a poem in French by Eiji Suzue. One resists, one fights against it, one seems not to recognize one’s own language anymore…It is insufflated with a spirit that gives it a physiognomy I didn’t know it… Yet something in the language allows it to function, and progressively, word after word, the poem falls back on its feet. One experiments in Eiji Suzue’s art a kind of resultant, which would be like a reality in suspension coming from the reaction of two different movements that equilibrate themselves as they progress.The question Kunitomo Emori asks in his text “Who is touching the sleeve ? ” seems to include in a same elan the poem and his reader, each one playing his role of partnership. Eiji Suzue’s words in French are more than a translation, they are a language which acts on another and carries us in its current. my / light / yet / luscious / beauty trudge / her / garden play / in / our / rain sweat / in / an / essential / moment This “Refregirator Poem” by Carol Kinne is one of the five shown here. In a letter to the gallery, Robert Huot says : “A few years ago Carol got a package of magnetized words that she stuck to her refregirator. The words were arbitrarily “selected” by the manufacturer (by number or weight—who knows ?) She occasionally moves them around to form new “poems”.” —Don’t you agree with me that their wind of freedom, humour and intelligence is a must to the exhibition ? The edition "Während 34 Tagen” (During 34 days) by Walter Janßen and Martina Klein has pages to be turned over. At the end of their common exhibition at the gallery in 2004 they wanted to mark the time of this intense artistic dialogue of their very beautiful exhibition. They combined the images of the exhibition with the time of the newspaper. Their choice turned to the newspaper the most largely representative of the French Press for two German artists, Le Monde. The period of the exhibition was covered by 34 issues of the daily paper. Between the pages of each newspaper they inserted the same 8 photos of the show. Their intervening seem almost being part of the original newspaper, still it creates a surprise and arouses a number of interrogations. For instance : Is the mobility of the page I hold in my hand of the same nature as the detachment of Martina Klein’s red painting ? Does the news of the page I just turned over inscribe in my memory like the aluminium cylinder inscribes his trace on the plaster of the gallery wall ? How do my memory and attention renew itself at each new page ? Is the artwork part of the world in which we live or is it something apart? Does the artwork express is itself on its own or does it need an apprenticeship of the eye ? Is an artwork next to another artwork telling something ? What do they mean ? What is the present-day question of an artwork ? What painting means today ? And sculpture ? Does the artwork belong to a geography ? An economics ? A politics ? How does it relate to me ? In the context of this exhibition, this edition takes a particular value, like a call to art here and now. The issue exhibited here is the number 5/34, corresponding to the paper of Saturday October, 23, 2004. In reply to this text I sent them, Martina Klein and Walter Janßen wrote : “the edition “Während 34 Tagen” is made by Walter Janßen and Martina Klein. If you feel like speaking about it, it is your decision.” The English texts of Robert Huot come together with French translations which were made since the first presentation of Robert Huot’s work at the gallery, in October 2005. It is difficult to summarize all those texts as they contain a lot of information and deal with many aspects of his work. But they are all centered toward the art and life of Robert Huot and go directly to the heart of the matter. They were written for the most part by Robert Huot and Scott Macdonald, historian and critic of exprerimental filmmaking. Robert Huot made painting, being among the first artists of Minimal Art, then films, happenings, music, installations. The variety of media he uses and the diversity of his investigations and artistical languages may disorientate the spectator. He dealt as well with the most radical abstraction as with the most psychological figuration, the disappearing of the subject as the narration of the diary, the most advanced modernity as the most burried archaism, the most personal art as the most politically committed, the gesture of the hand as the play of the machine, the order as the chaos. Robert Huot seems to welcome everything in his art and to want to escape a single understanding. Yet his work is there before our eyes, with a neat and precise outline and a shape without ambiguity. And it is astonishing to see that this multiplicity define in the time a strong coherence, like a new work which would bring new and unexpected perspectives to the rest of the previous works. It stroke me when Robert Huot came to Paris that he says finally consider himself a painter, and insisting that his painting is not easel painting. These texts cover a large itinerary of Robert Huot’s production. I was very happy to translate them as they make enter into the life of the context which began in the end of the 50’s in the US and was a very great artistic time. Here is an excerpt of The Art of Context. It is Robert Huot’s speaking : “First I have to open the window of time wider. When I think of the issues of art I must go back to 50’s and the days of 10th Street in N.Y.C. I was a young man infatuated with the life of an artist, hanging out with the 10th Street artists—closing the Cedar Bar—talking all night about art and politics—being a rebel yet being part of a cause (what I see now as a growth industry) what I saw then as an intoxicating way of life—bohemian—radical—far different from my father’s six days a week of enslavement. The New York School was in its hey-day and I was a small part of it. I went to every show, every opening and every party. Soon I knew everyone (the art world was smaller then.) I worked in my studio 14 hours a day—made more paintings than anyone I knew—held down a full time job. I didn’t sleep much—just worked and partied. For about a month each year I’d collapse, then build myself up for the next stretch of art and madness. It was great—I was young—I had no one to worry about but me and I didn’t worry much about me—I was an artist—period. So I entered my art life with a kind of religious fervor (though most secular.) I went rapidly from “apprentice” to “journey-man” and began along with many others, to develop a style to rival abstract expressionism—what was soon to be called “minimal art.” Minimal art from my point of view was a style of efficiency—direct—color, shape, size, location, surface and light—what you see is what you get. A reaction to the “automatic writing”, the idiosyncratic nature of the then dominant style of abstract expressionism. We hoped to present the reality of the elements of art as a language that spoke directly to the viewer. These were not new ideas, but they seemed fresh and necessary in the seeming muck of the moment.” It is little by little that Paul Nelson’s poetry found its way in the gallery. The “awareness”, as it were, is during a work of translation. I told myself his words “hold” in the memory the way some paintings “hold” on the wall… It appears to me his poetry doesn’t search for the spectacular. It says in the simpliest and the most direct manner something that happens, something which exist and says it with the very reality of the thing. Perhaps could we speak of a poem-object, as the achievement of an enormous work which makes of the precision of the word he uses the exact equivalent of the reality it conveys. And it seems to me his poetry finds its place on the wall, not because of any visual effect that would come from the composition of the poem, but because the whole poem is itself plastic, it is a united form which moves in space and time. SCARP by Judith Nelson combines various natural materials : Red dirt carapace prints on hand-made paper, Haole Koa pods, Haleconia pods, Norfolk Pine pods. Here is what Judith Nelson says in an e-mail to the gallery : “ “red dirt” refers to the ink I make from grinding local soil, high in iron content, and then printing with it on my handmade papers. The printing “block” ieither the large pod from a Royal Poinciana or the dried carapace of Hawaii’s spiny lobster. “Haole koa” pods and Norfolk pine pods are from trees. The haleconia is a broad leaf plant that grows just outside our back door.” And on a more general matter, Judith Nelson adds : “My art is not intended to be controvesial or definitive. It embraces my questions and explorations with implication toward awareness of how my response to specific location is shared with others, and theirs.” SCARP by Judith Nelson was the first to find its place in the mounting of the exhibition. It gave the tonality or the bass of the exhibition. It offers the preceding words another mode of relation, as a release of their weight, and as a meeting point of what their many tracks strive to make in the ground, brings them together, puts the tune on, lights up their feet, and opens the dance floor. Here are two responses by Paul and Judith Nelson to what I wrote about their work : Paul Nelson : “Your careful and incisive appreciation of my poems, never mind the fine translations, finds me impressed by own work …seldom my usual feeling.” And Judith Nelson : “I enjoy your metaphors for my work: music and motion. This is just right, with the meter and spaces for the eye to traverse in my piece.” Thank you. © 2007 Arnaud Lefebvre and Rosemarie Castoro, Kunitomo Emori, David Gordon, Robert Huot, Walter Janßen, Carol Kinne, Martina Klein, Paul Nelson, Eiji Suzue, 2007. Translations: Arnaud Lefebvre, David Gordon, Rosemarie Castoro. LIENS / LINKS: Rosemarie Castoro: http://www.rosemariecastoro.com Rosemarie Castoro "A Day in The Life of a Conscientious Objector": http://rosemariecastoro.com/72A%20DAY%20IN%20THE%20LIFE%20OF%20A%20CONSCIENTIOUS.pdf Robert Huot: http://www.roberthuot.com Carol Kinne: http://www.carolkinne.net Paul Nelson: http://pages.prodigy.net/sol.arts.editor/entry.htm Eiji Suzue: http://www.k3.dion.ne.jp/~suzueiji/ |

Exhibit Images  "Une journée ..." Vue d'ensemble  "Une journée ..." vue gauche: Rosemarie Castoro, David Gordon, Kunitomo Emori, Eiji Suzue, Carol Kinne  "Une journée ..." vue face: D. Gordon, K. Emori, E. Suzue, C. Kinne, W. Janßen, M. Klein  "Une journée ..." vue droite: P. Nelson, J. Nelson  ROSEMARIE CASTORO "A DAY IN THE DAY OF A CONSCIENTIOUS OBJECTOR", 1969, 24 poèmes n°1/24 à 24/24, xerox, 122 x 147 cm © Rosemarie Castoro  DAVID GORDON Poème "The Survival…" , 2007 © David Gordon  EIJI SUZUE, KUNITOMO EMORI Kunitomo Emori: Texte sur la poésie de Eiji Suzue, avec Notes de Eiji Suzue © Kunitomo Emori, Eiji Suzue  CAROL KINNE "Refregirator Poems" : ‘I Recall a Woman Dream’, ‘Blue Sausage Moon Over Red Sea’, ‘My Light Yet Luscious Beauty’, ‘You Worship the Delirious Goddess Under White Fluff’, ‘Cool Milk Void Beneath TV’. © Carol Kinne  WALTER JANßEN, MARTINA KLEIN Whärend 34 Tagen, n° 5/34, 34 Exemplare vom 19 Oktober bis zum 27 November 2004, Eine Edition von Walter Janßen und Martina Klein zur Austellung bei Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre. © Walter Janßen, Martina Klein  ROBERT HUOT "An Interview with Robert Huot by Scott MacDonald", "The Art of Context", "Film Information". © Robert Huot, Scott MacDonald  PAUL NELSON 5 poems : "Burning the Furniture", "Cloak", "Children Will Break Windows", "Sit Still", "Dawn Walk". © Paul Nelson  JUDITH NELSON "SCARP", 2006, Red dirt carapace prints on hand-made paper, Haule Koa pods, Haleconia pods, Norfolk Pine pods, 22” x 26” x 3”. © Judith Nelson |